All Day Articles[1].Pdf Dad In France

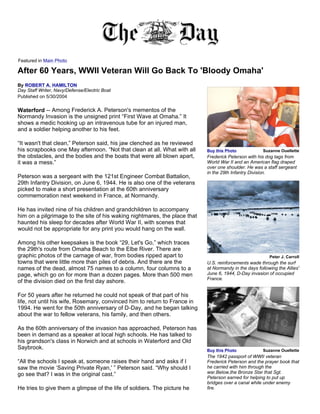

- 1. Featured in Main Photo After 60 Years, WWII Veteran Will Go Back To 'Bloody Omaha' By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 5/30/2004 Waterford -- Among Frederick A. Peterson's mementos of the Normandy Invasion is the unsigned print “First Wave at Omaha.” It shows a medic hooking up an intravenous tube for an injured man, and a soldier helping another to his feet. “It wasn't that clean,” Peterson said, his jaw clenched as he reviewed his scrapbooks one May afternoon. “Not that clean at all. What with all Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette the obstacles, and the bodies and the boats that were all blown apart, Frederick Peterson with his dog tags from it was a mess.” World War II and an American flag draped over one shoulder. He was a staff sergeant in the 29th Infantry Division. Peterson was a sergeant with the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion, 29th Infantry Division, on June 6, 1944. He is also one of the veterans picked to make a short presentation at the 60th anniversary commemoration next weekend in France, at Normandy. He has invited nine of his children and grandchildren to accompany him on a pilgrimage to the site of his waking nightmares, the place that haunted his sleep for decades after World War II, with scenes that would not be appropriate for any print you would hang on the wall. Among his other keepsakes is the book “29, Let's Go,” which traces the 29th's route from Omaha Beach to the Elbe River. There are graphic photos of the carnage of war, from bodies ripped apart to Peter J. Carroll towns that were little more than piles of debris. And there are the U.S. reinforcements wade through the surf names of the dead, almost 75 names to a column, four columns to a at Normandy in the days following the Allies' page, which go on for more than a dozen pages. More than 500 men June 6, 1944, D-Day invasion of occupied France. of the division died on the first day ashore. For 50 years after he returned he could not speak of that part of his life, not until his wife, Rosemary, convinced him to return to France in 1994. He went for the 50th anniversary of D-Day, and he began talking about the war to fellow veterans, his family, and then others. As the 60th anniversary of the invasion has approached, Peterson has been in demand as a speaker at local high schools. He has talked to his grandson's class in Norwich and at schools in Waterford and Old Saybrook. Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette The 1942 passport of WWII veteran “All the schools I speak at, someone raises their hand and asks if I Frederick Peterson and the prayer book that saw the movie ‘Saving Private Ryan,' ” Peterson said. “Why should I he carried with him through the go see that? I was in the original cast.” war.Below,the Bronze Star that Sgt. Peterson earned for helping to put up bridges over a canal while under enemy He tries to give them a glimpse of the life of soldiers. The picture he fire.

- 2. paints is not one of rugged heroes storming a hill for the glory of their unit. Rather it's of men trudging across a broken land, taking cover when the enemy opens fire and trying to keep up their strength so they can keep going. “You slept when you could lie down, and you ate what you could — K- rations usually, D-bars (chocolate) when we had them. A stray cow once. We came across a chicken farm, and I boiled about eight eggs in a big tin can. Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette “When they ask me questions, I try to give them honest answers, The dog tags and bronze star sit amoung without being too gory. I don't want to tell an 8- or 9-year-old about the memorabilia of World War II veteran arms and legs lying around the beach, or the sea red with blood. I tell Fred Peterson at his Waterford home them what I can, what I think they should know. Thurs., March 25, 2004. Peterson was a staff sargeant who was on the second wave that stormed the beaches of Normandy with “Bloody Omaha, they called it, and that more or less summed it up. the 29th Division Association; he is one of You used bodies for cover, because they were gone anyway. Guys 35 in his company to come home. He found were screaming for help, but they told us to ignore them and save the Nazi flag in the office of Joseph Goebels, the Nazi regimns Minister of ourselves, and our rifle, and keep going. They were telling us to let the Propganda, in Germany in 1944. medics take care of them, but most of the medics were gone, too. There wasn't much we could have done for them. “I remember one sergeant got up and was yelling, ‘C'mon, c'mon,' and the next thing I knew the whole side of his face was gone. I don't tell those stories. I tell about the time we got hold of some good wines in a German wine cellar that was as big as my house. We stayed there for a while, let me tell you.” Peterson, who is now 83, earned a Bronze Star for helping to put up some bridges over a canal, which allowed his unit to enter Germany in the early days of April 1945. The citation says he exposed himself to enemy fire to complete the mission. “It was almost funny, really,” he said. “We could see them on the other side. They had this fire going. They were cooking. And they were close enough for us to talk to them if we knew the language.” Every now and then, the Germans would take up arms and shoot at the engineers, who would retreat as infantrymen returned the fire. After a few minutes, the Germans would go back to their meal and the engineers would get back to work. There was nothing heroic about it, Peterson said, or about the Presidential Unit Citation his unit earned in the invasion. “All the medals I got, and 75 cents, will get you a cup of coffee. In my mind, the heroes are still over there. There are three cemeteries over there loaded with them. I wasn't a hero. I was just one of the lucky ones.” ••• Peterson's children grew up familiar with a man who worked at Pfizer, an image that was hard to reconcile with someone who had taken part in the Normandy invasion. But the Peterson household on Brill Street in Waterford held some reminders of war, all of which Frederick kept in a closet: a Nazi flag ripped from the headquarters of Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's minister of propaganda; hats that belonged to an SS trooper and a German officer; a German bayonet; and a shoe mine – a crude wooden device designed to blow off a foot to cripple a soldier to make him a burden for the rest of his unit. Peterson's three children started to learn of his war experiences only a decade ago. “I knew my father had been in World War II, but I had no idea of the details,” said his daughter, Kris Peterson- Browning, who lives in Norwich. “That movie, ‘Saving Private Ryan,' it was tough to sit through once I understood the story was so similar to what my father lived through.”

- 3. His son, Vaughn Peterson of Waterford, said that if you watch the movie closely you can see the arm patch of the 29th Division on some of the soldiers. His father's group blew a safe path through the minefields for the Army Rangers, who were the focus of the movie. After the 50th anniversary of D-Day, Vaughn Peterson began assembling maps of the beaches, pictures of the fortifications and other images of the invasion, so that he could talk it over with his father. His father recognized one photograph of a pillbox as the place where Germans fired on his unit as they tried to come ashore. It was also the target of his first shots from his M-1 rifle. “I was always proud of my dad because he fought the Nazis,” the younger Peterson said. “He was the best father in the world before I found out all this, but I had a much greater appreciation of the depth of this guy afterwards. Think of what he went through, and he was able to retain his values, retain his sense of humor, retain his appreciation for the value of life, and pass all of that on to us.” Vaughn Peterson is also a military veteran. Though he never fought in a war, he knew a lot of men who served in Vietnam and later suffered emotional problems, in part because of their war experiences, but also because of their treatment back in the United States. “Dad's character was intact before he went, stayed intact while he was over there, and was intact when he returned.” Peterson-Browning's husband, Max Browning, a videographer, will document the trip to France this week. “I want to see the towns my father has talked about over the last 10 years,” she said. The 29th liberated 10 French towns in the first few days of operations. “But of course, I also want to see the beach. The infamous beach.” Her 11-year-old son Trevor wants to see the cemetery that his grandfather talked about in his class this year. “I had hoped to go there when I was older, so I could see it for myself,” Trevor said. “But it's going to mean a lot more, knowing that he was there in the war and now he's going to be there with me.” Peterson's wife, who convinced him to make the first trip back to France a decade ago, died in 2002, just two months after their 60th wedding anniversary. Peterson's other daughter, Marlene Lord, and her son Alex will make the trip, along with Vaughn Peterson's adult son, Matthew. Also in the family group will be Peterson-Browning's other son, 9-year-old Niles, who is looking forward to seeing some of the French landmarks. “I want to go to the Eiffel Tower,” he said, “and eat some weird French food and have a good time.” ••• Peterson was drafted into the Army as the war began. Following six months of maneuvers in the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida, his division shipped out to Europe on Oct. 5, 1942. They arrived off Gourock, Scotland, six days later, and then went by train to southern England, where he was assigned for a year to guard the coast against German invasion. An engineer, he had to destroy the German mines that occasionally would wash ashore. Also, he and the others had constant training. One night on a river-crossing exercise a boat capsized, and the unit lost 14 men. Others were killed or wounded in live-fire exercises. He would get an occasional 48- or 72-hour liberty, and he made a couple of trips to London. Mostly he kept company with George O'Brien, who like Peterson was married. Instead of chasing girls in the nearby town, they

- 4. would get a cold beer at the canteen on base, or play baseball or football. One of their favorite pastimes was to watch movies, though today the only one he can remember is “Sunday Dinner for a Soldier,” starring Anne Baxter and John Hodiak. It's about a poor family in Florida that saves all its money to spend on a soldier they have invited to Sunday dinner. He lost track of O'Brien after the invasion. At a 29th Division reunion several years ago, he learned that O'Brien had been killed on June 10, just four days after they attacked. In the fall of 1943, their training changed. Bulldozers would plow holes the size of a Higgins Boat, an amphibious landing craft, and the men in his unit would practice charging out of them. Though the invasion was only a rumor then, they realized they would take part in it. “Even on Sundays, I can remember going off on a hike, and we'd do 12 miles before dinner. Everyone knew we were getting ready for the invasion, but nobody knew when.” Early on the morning of June 5, 1944, his unit loaded into the USS Samuel Chase, a troop transport, and headed across the English Channel. Foul weather thwarted plans to invade that day. But at 2:30 in the morning of June 6, they were told to grab everything they could and prepare to hit the beach in the second wave, at about 7 a.m. ••• It was the largest invasion force ever assembled. More than 1,000 troop transport aircraft dropped paratroopers behind enemy lines. Bombers unloaded 5,000 tons of high explosive weapons. Eight countries supplied the 1,213 warships and the 4,126 amphibious craft that landed 130,000 troops. The British and Canadians landed at Gold, Juno and Sword beaches. The Americans were at Utah and at Omaha. The ships were so close together, Peterson said, it looked as though you could have walked across the channel without getting wet. Omaha was a 31/2-mile stretch of sand that ended above the high tide mark either in rock cliffs more than 100 feet high, or in enemy strongholds. Peterson was ordered over the side of the Chase and down into a Higgins Boat that was being tossed by the waves. He tried to time his jump so that he would land as the boat reached its peak. Once he was aboard, he saw soldiers getting sick, some from the motion of the bobbing Higgins Boat, others from sheer nervousness. There were 45 men kneeling behind the precious armor that protected them from the bullets and artillery shells they heard whizzing by as they approached the shore. Then the boat scraped bottom, and the boatswain's mate dropped the hinged front section into the waist-deep water. “We're sitting ducks,” Peterson said. “When that ramp goes down, you're on your own. You do all you can to stay alive. As soon as the ramp comes down, you charge out of the water. Boats are getting blown up right and left, so nobody stays in it long. You see those boats taking a direct hit, and you hope you're not going to be one of them. “I was 23 when I hit the beach, and I think I was 43 by noontime.” His unit went ashore at Dog Green, the second most westerly of eight assault zones. Their orders were simple: make for the church steeple at Vierville, and get as far as you can. He went ashore with his M-1, two bandoliers of .30-caliber ammunition and a cartridge belt — a couple hundred rounds in all — and two grenades. He did not have a sidearm at that point, but he would have his pick of pistols, rifles or anything else once they got to the beach. His rifle jammed, and he picked up another, a bolt-action Springfield, which served him well in

- 5. the weeks to come. Off the beach, barges loaded with rockets fired in to soften up the resistance. Also offshore, destroyers sailed back and forth, many dangerously close to shoal water, lobbing artillery shells into the German encampment. Farther off, battleships fired their 16-inch guns, putting shells the size of Volkswagen Beetles onto the beach. Rifle and pistol fire, Thompson submachine guns, and grenades added to the cacophony. It was too noisy to hear what anyone was saying, too noisy to hear yourself think. Confusion reigned. “There were so many men shooting, you don't know who's doing what,” Peterson said. “I could have killed 10 men. I could have killed 100. I just don't know.” He knew from his training that when someone trains a mortar on you, the first two shots generally miss. But an expert crew will use those shots to zero in on a target, so when the second shell lands, you should be up and running. “You train, and it's instilled in you to save your own butt, somehow, because as long as you're alive you can fight,” Peterson said. “But I still can't believe what I did.” The 121st Engineer Combat Battalion worked its way up the beach. At the end of the day he was ordered to take three men to find a spot for some tanks and other vehicles to come ashore. Early in the morning of June 7, they fought their way back, only to find their unit under heavy attack and no way to rejoin it. They took shelter in a cemetery, hiding behind gravestones. Then they hid in a chicken coop, spreading feed for the birds so they wouldn't squawk and give them away. Later that day they joined up with another unit and were assigned to a machine gun crew. On June 8, they rejoined the soldiers of their original unit. “By that time, out of 200 who landed, I think there were 35 left,” Peterson said. “Thirty-five out of the whole bunch.” ••• The next six weeks were a blur of Germans to fight and towns to liberate. His battalion saw 44 straight days of combat before they got a break. He remembers being interviewed in the town of St. Lo by a reporter with The Boston Globe. And he remembers meeting up several times with his younger brother, Lawrence, who was with the 2nd Armored Division, as their respective units marched through France, Holland and Germany. He turned 24 years old on June 15, but he didn't even remember it was his birthday until much later. His wedding anniversary came four days later. On his first anniversary, he had arranged from England to have flowers sent to his wife. On his second, he didn't have time to write a note. He recalls at one point running into a unit of replacement troops, their guns gleaming, their faces shaved, their uniforms clean, and he realized just how bedraggled his unit looked. They spent the days of Aug. 5, 6, 7 and 8 liberating Vire, about 12 miles inland, south of the invasion. This week, he will stay in a hotel in that town. The battalion liberated a slave labor camp, where a group of workers from Poland were housed in two small buildings with bunks stacked four high against all the walls. When they threw open the gates and told them to go home, the workers stood there listless. They had no homes to return to. Within weeks they were meeting Russian soldiers on the Elbe River in Germany. On May 9, 1945, they were on the outskirts of Bremen, Germany, as the end of the Third Reich was heralded around the world. But even after the war, Peterson recalled, a colonel and his driver were killed when their Jeep ran over a mine. “I

- 6. wasn't going to feel safe until I was back in Connecticut,” he said. He returned to France in a boxcar, was paraded through the streets of Paris, then boarded the Santa Rosa, a cruise ship converted to troop carrier, which made a rough ocean crossing to New York. In the city, there was another parade. “It makes me feel proud to have been a part of it,” Peterson said of the war. “I wouldn't want to do it again, but it was an experience.” ••• “W “When I first got home, I didn't even want to go see the fireworks shows with the kids, they'd scare me so much,” Peterson said. “I wouldn't even go to air shows, or parades. My wife used to take the kids. I go now, because it's been 60 years, but it took a long time.” Peterson also struggled for years with feelings about being one of the few from his unit to come home — survivor's guilt, we know now, though it didn't have a name in 1945. “I would wake up at night and think, ‘My God, I'm home. What am I doing here?' It gradually goes away, but to this day if I wake up at night I lie there thinking about it.” He went back to work for the railroad, then took a job as a lab technician in the research department at Pfizer in Groton. After his first two children graduated from Waterford High School, he moved to Ledyard, then back to Waterford after he retired in 1985. In the early 1990s, when his wife raised the subject of the 50th anniversary, he first rejected the idea of returning to France. But she wouldn't let it go, and he finally relented and agreed to take her there. He was one of five men from his unit who attended the 50th reunion in Normandy. The 29th Division Association signed up more than 700 people for the trip. “It turned out to be a good experience. You never saw so many grown men crying in your life. If I'd had to go alone, I never would have gone, but I'm glad she didn't give up.” For that commemoration in 1994, France closed the schools so children could take part in the parades. Mayors of the towns in the region all wanted to host thank-you dinners for the veterans. “Even in Paris, I flew out of Orly and the girl at the desk checking our bags looked up at me and asked, ‘American soldier?' And I said yes, and she said, ‘Thank you very much.' ” Today, 10 years after that welcome in France, he has a nagging doubt about going back again. This time the 29th Division Association has signed up just over 300 people, including spouses, and Peterson is worried he won't see anyone he knows. The four others from his unit who attended the 50th anniversary have died. Also, he worries about the memories of war. “It's been 60 years and the mines would all be rotten by now, but you still worry. The picture is still there, in your mind .... ” © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 7. Featured in Main Photo Revisiting The Longest Day D-Day Veteran Was Part Of The Great Invasion By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/3/2004 Vire, France Looking out over a field of long grass in the south of Normandy, Frederick A. Peterson was reminded of a time 60 years ago when it was not so bucolic, when the conditions making it a beautiful pasture also made it a crucial battlefield. Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette “I can just picture the whole battalion of Patton's tanks coming across Above, Frederick Peterson studies the that field, it's so nice and flat,” said Peterson, a Waterford resident who passing landscape as he travels by bus to Vire, France, where he and his family, along was part of the 29th Infantry Division when the Allies stormed ashore with other veterans, are staying while on France's northern beaches on June 6, 1944. attending ceremonies marking the allied invasion of France. Sitting behind Peterson Not far from the hotel where Peterson is staying this week is Hill 203, is his grandson, Alex Lord. where the 29th spent many hours and sacrificed many men while trying to seize the strategically important ground. Peterson has promised his grandchildren and other relatives who came with him from southeastern Connecticut that he will try to find a particular farm. It was there, while on a scouting mission, that he and a few other soldiers hid from the Germans in a chicken coop. Although Peterson had been back in France for only a few hours, he felt more at peace with the memories of war than he expected. Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette “Everything has changed so much. A lot of the places in Vire weren't ‘People ask me all the time if I remember even here when I came back for the 50th anniversary,” said Peterson, such-andsuch a town, but the only ones I who made his first return to Normandy in 1994. recall are the towns like Vire or St. Lo, where there were big battles.' He was surprised to see that Office Depot, a chain business dotting many malls in the United States, has a large store here and that Cushman & Wakefield is dealing in French real estate. He took note of a Courtyard of Marriott near Charles de Gaulle Airport, where his family landed early Wednesday. The countryside between Paris and Vire is largely rolling farmland and forest, with few reminders of how badly it was scarred during the violence of the Nazi occupation and its retaking by the Allies during World War II. Ap Peterson was with the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion, which was Above, carrying full equipment, American supposed to blow a hole in the wall at the western end of Omaha assault troops move onto a beachhead, Beach in Normandy, breaching it so that tanks, jeeps and trucks could code-named Omaha Beach, in this June 6,

- 8. get through. 1944 file photo, during the Allied invasion of the Normandy coast. Frederick Peterson He recalls tanks outfitted with rams to punch holes through earthen was with the 121st Engineer Combat berms. Once the tanks had done their work, he and the other combat Battalion, which was supposed to blow a engineers would run in with TNT to blow holes in the barriers large hole in the wall at the western end of Omaha Beach, breaching it so that tanks, enough to get the tanks themselves through. jeeps and trucks could get through. The ground has long been graded and reseeded. But the landscape is dotted with memorials to the sacrifices of allied soldiers, and everywhere there are banners and posters proclaiming the anniversary. “Of course it all brings back memories,” Peterson said. “But it also makes me realize how lucky I was.” •••••• Peterson, three of his children and four of his grandchildren are touring Normandy during the 60th anniversary observances. On Sunday he will be one of the veterans to make a short presentation at a commemoration. Many expect it will be the last large gathering of D-Day veterans; Peterson will turn 84 this month, and many of the other veterans are older. The 29th Infantry Division Association signed up more than 300 for the 50th anniversary, but the number has dwindled to just 75 this year. On Tuesday, at Boston's Logan International Airport, Peterson showed up more than two hours before his flight was to leave just to see if he recognized anyone else heading for France. He wore his 29th bolo tie clasp to identify himself. He saw just two other veterans of his division, one walking with a cane, the other in a wheelchair. He had better luck at de Gaulle, where he spotted a few people wearing 29th ball caps. He rushed to greet them. “What unit were you with?” they asked one another almost simultaneously. Soon he had hooked up with Frank Marino, who lives on Long Island and was with the 227th Field Artillery. He also found Don Mellon, a radio operator and forward observer with the 116th Artillery who lives in Stony Point, N.Y. They traded favorite stories about Gen. Charles “Zippy” Gerhardt, beloved by the men despite being a stickler for regulation. “Even in combat he used to come around and see if there was mud on the undercarriages of our jeeps,” Marino said. “He wanted all the equipment to be clean, no matter what.” “He insisted that all of us be wearing our chinstraps on our helmets,” Mellon said. The precaution made the helmet more uncomfortable, but it could save a soldier's life in combat. Marino recalled running for a foxhole one day early in the invasion when the Germans attacked with their deadly accurate 88mm artillery. He was yelling at a guy he thought had stepped on his hand. It turned out shrapnel had shredded his hand and the back of his knee. Mellon's part in the allied invasion came a bit later. He arrived a few weeks after D-Day, immediately after finishing 17 weeks of Army basic training and 13 weeks of advanced schooling for radio operations. He joined the unit in Brest, as it charged through central France. “So you were in Fort Benning (Ga.) on June 6th?” Peterson asked as Mellon replied with a nod. “I would have traded with you, no question about it.” While the replacement troops did not have the battle experience of men who had been in Normandy since the initial landing, Mellon said, they caught on quickly. He remembers his first day, when a sergeant told him to dig a foxhole and he dug one that seemed adequate — until the German 88s opened up that night. The next morning

- 9. he dug it a little deeper. And the morning after that, he dug deeper still. He and the other replacements, he said, felt no resentment from the soldiers who had survived the grisly days and nights of fighting and slaughter. Mostly, he said, the men who had been out of touch with their families for several weeks were just wondering what was going on back home. At de Gaulle airport, where others were reuniting, several women wearing insignia of the 29th Infantry Division Association auxiliary approached Peterson to ask about his wife, Rosemary, who died in 2002. “They were all active in the auxiliary together,” Peterson explained. “We'd been to reunions in Boston, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Washington, D.C. She used to get more excited about the reunions than I did. I'd tell her, ‘You want to go, just make reservations for two. I don't care where I go.' ” He is worried about the short speech he is expected to give on Sunday, before a crowd assembled at Omaha Beach. “I still don't know if I'll be able to do it,” he said. “It'll be a little emotional, I imagine. Tough to forget all that happened, you know?” •••••• Touching down at the airport just outside Paris, Peterson couldn't recall much about his first trip to the French capital 60 years ago. He spent part of it in the back of a covered truck, probably sleeping, because in those days soldiers slept when they could. “That's when things were moving fast,” he said. “In fact, they were moving so fast the tanks got so far out in front of everybody we couldn't get them enough gas to keep them going. ... “People ask me all the time if I remember such-and-such a town, but the only ones I recall are the towns like Vire or St. Lo, where there were big battles.” But he recalls his second trip to Paris. With the war winding down, he and a few other men from his unit got a 72-hour pass and traveled to Paris from Germany to see Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower and some other sights. When they arrived they learned that the Glenn Miller Band was playing, and he decided to take his men to see the show. When a young lieutenant stopped them at the door and told them battle garb was not appropriate, Peterson sought out a more sympathetic major and asked him to overrule the lieutenant. “We did look crummy, just back from the battle zone,” he said. “But he got us seats, about five rows back from the stage.” Six decades later, Peterson is organizing another outing, this one involving his nine relatives. The strategy for keeping everyone together at the airport was not easy, particularly when one headed off for a bottle of water, another went looking for a bathroom and a third decided to check out a pastry stand. “Things are more confused now than they were on D-Day,” Peterson sighed with mock exasperation. “That's what comes of being a platoon sergeant, I guess. You learn to take care of your troops.” b.hamilton@theday.com © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 10. Featured in Military 60 Years Has Not Diminished Appreciation By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/4/2004 Vierville sur Mer, France As he walked down the street after dinner one evening this week, Frederick Peterson was surprised when a Frenchman rushed up and hugged him. “He was saying, ‘Thank you, thank you,' ” said Peterson, a veteran of the Normandy invasion. “Even after 60 years, they really appreciate what we did. It makes you feel good.” Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette D-Day Above,Frederick Peterson inspects a There have been dozens of shows of gratitude since Peterson arrived. commemorative bottle of Calvados presented to him by the Mayor of St. As the veterans left an observance ceremony at the National Guard Laurent sur Mer during a luncheon on Memorial on Omaha Beach, French soldiers in full uniform saluted Thursday honoring American veterans of their van. The city of Vierville sur Mer hosted a luncheon in their honor the Normandy invasion. Peterson said he Thursday in a pavilion on the beach, where they were presented with a remembers the liquor well from his service certificate of appreciation, a vial of sand from Omaha Beach, and a days in 1944 France. grab-bag of goodies that included local candies and a bottle of a popular local apple brandy. And as they left the luncheon there were local residents lined up like groupies at a rock concert, hoping for a chance to shake the hand of one of their village's liberators and struggling to explain through the language barrier that they would be honored to have their picture taken with one of the veterans — with the beach as a background. And the appreciation extends beyond the Normandy coast. Peterson's son, Vaughn, said he is friendly with a couple that live in Belgium who will be making a five-hour drive today just to meet his father. “They were adamant about making the trip just to see him,” the younger Peterson said. The mayor of Vierville sur Mer, and the entire city council, turned out to dine with the veterans, and the mayor greeted every veteran reboarding the bus afterward. “I wish from the bottom of my heart that your children, and your grandchildren and your friends who are with you today, know how much we appreciate you,” the mayor said during the luncheon. “Thank you for bringing freedom and democracy back to France.” Robert A. Hamilton © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 11. Featured in Main Photo Back To Bloody Omaha D-Day Veteran Spends Emotional Day In Normandy By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/4/2004 Vierville sur Mer, France The first shot Frederick A. Peterson fired in combat was aimed at some German soldiers in a pillbox high on a cliff overlooking Omaha Beach on D-Day. On Thursday, as Peterson revisited the beach and found the pillbox Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette intact although badly weathered, memories of the friends who were D-Day veteran Frederick Peterson, right, lost under the withering fire came rushing back. and his grandson, Alex Lord, walk among the grave markers at the American cemetery at Colleville sur Mer, Normandy, As the 29th Infantry Division rushed the beach just after dawn on June on Thursday. Many of Peterson's comrades 6, 1944, Germans poured out of the pillbox — a low, enclosed gun who died during the Normandy invasion are encampment made of reinforced concrete — firing down on the men, buried here. taking a terrible toll. “That's it, that's where we lost most of them,” said Peterson, a Waterford resident, standing almost exactly where he came ashore 60 years ago. His eyes grew misty and his voice cracked. “I knew I should have stayed home,” said Peterson, who is 83. “Here goes another night's sleep. I'll have to have a glass of wine before I go to bed.” Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette ‘All the little kids used to come stand by our As Peterson's children and grandchildren climbed a path and garbage cans looking for food. I would disappeared into the vacant fortification, the smile that usually adorns always save them a little bit. They had his face vanished. His bright eyes narrowed and his brow furrowed. nothing.We used to get a ration, cigarettes, some gum, a candy bar. I would keep the cigarettes and give them the rest.' Frederick “They shouldn't be up there,” he snapped. But his mood lightened and Peterson his smile began to creep back as he realized that the way he remembers it is not the way it is today. “I don't know. I just don't know. I can connect to that pillbox too easy,” Peterson said. “I wouldn't go near it.” His family had a connection to the pillbox as well, but not the same kind. Peterson's 57-year-old son, Vaughn Peterson, said that for the last 10 years, since his father finally began talking about the war after a half-century of silence, they have heard tales of the pillbox and how it was his father's first target. “It's exactly like he always said,” Vaughn Peterson said. “It's a concrete image of all he's talked about.” And he admitted that it gave

- 12. him a bit of a chill. “It's one thing to see the cinematic version, but to be here and see the trails up the cliff, to see the lines of fire the pillboxes have, that's something else entirely,” he said. Grandson Matthew Peterson agreed: “It was emotional, unbelievable really, to comprehend that he was here 60 years ago, in a completely different situation. There were a bunch of Germans up there then, and Grandpa probably took out a good number of them.” Grandsons Trevor Browning, 11, and Niles Browning, 9, summed up the experience of entering the pillbox with single words. “Weird,” said Trevor. “Freaky,” added Niles. As the senior Peterson began to make his way off the beach and back to the tour bus, two French fighter jets screamed over the beach, wagging their wings in a salute to the 75 veterans of the invasion gathered there. “Thanks, fellows,” Peterson said, his smile returning. “Where the hell were you on D-Day?” Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette Frederick Peterson, left, and Arden Earl, •••In a ceremony at The National Guard monument on the beach, both veterans of D-Day, walk along Omaha members of the 29th gathered to recollect their own tales of the Beach and talk about their role in the invasion. Charles Heinlein of Baltimore, a member of the 116th historic invasion six decades past in St. Infantry Regiment, said Omaha Beach was “a scene from hell ... so Laurent sur Mer on Thursday. many dead, so many wounded. It was total chaos.” Sixty years ago, German 88mm artillery shells were landing all around them as they rushed for the cliffs. “The concussion from the shells would numb you,” Heinlein said. “But the hot shrapnel would do a lot more.” John Burns of New York said he was supposed to be on Landing Team 2, but was pulled off that team because of an abscessed tooth. He returned to duty in late May and was reassigned to Landing Team 5. Team 2 went ashore as scheduled at 7 a.m. It was wiped out. Team 5's landing craft sank and all its gear was lost. The men were plucked out of the water by one of the thousands of Navy ships in the English Channel and sent back to England to be re-equipped. “How was I so fortunate?” Burns asked plaintively before a group of fellow veterans. “How did a 19-year-old kid end up in lucky boat team number 5?” John Fowler of St. Louis was with the 104th Medical Battalion. He joked that when the ramp came down at the front of his landing craft, he rushed for cover on shore so quickly his boots did not get wet. Medics suffered some of the worst casualty rates on D-Day, exposing themselves to enemy fire as they aided the wounded. But Fowler said he seemed charmed as he rushed from one broken body to the next. At one point, a shell burst nearby, injuring the man behind him, the man to his side and the man on the stretcher they were carrying to cover. Fowler was unscathed. But some of the worst trauma came from the injuries others suffered. One veteran of the 116th's headquarters company recalled watching as a tank rolled ashore and over an injured man, crushing him on the hard-packed sand.

- 13. “I wanted to help that GI get out of the way,” he said, tears flowing freely down his face. “I'm bothered to this day, thinking about what I could have done, even though I realize there was nothing I could do.” Another veteran recalled making for the cover of a stand of trees when snipers opened fire on his unit. Over the next 15 minutes the infantrymen shredded the trees so badly that they were defoliated, exposing two dead Germans who had tied themselves in place so they would not fall out if they were wounded. Around the tree, 15 of his comrades lay dead. But veteran Ivy Agee of Gordonsville, Tenn., said with each soldier lost the Allies gained a little ground. “We were tested to the limit, but each success gave us the courage to go on,” Agee said. “I was honored to be associated with such a fine group of soldiers.” He ended by invoking the 29th's motto: “29, Let's Go.” Norman Grossman of Newton, Mass., a member of the 116th's L Co., said one of his best friends never made it off the beach and another never made it to the top of the cliff. “Who would think on the morning of June 6 that we would make it through the day, and more miraculously, that 60 years later we would be here to remind the world of that great event and hope our country will never forget those who fell here?” Grossman said, choking back tears. ••• Members of the tour group left their hotels in Vire early Thursday and spent about an hour passing through French farm country, where the scars of war have healed and bright red, yellow, purple and white flowers grow in profusion. Peterson recalled using half-pound bricks of TNT to blow holes in concrete walls and earthen berms the Germans constructed to slow the American tanks. To blow a wall, he said, the men placed the blocks in an E shape, with the legs of the E pointing up in the air. Later in the war, he said, they used a block of explosives in a more benign, almost benevolent way: They spotted a couple fishing in Germany after the fighting ceased, so they lent a hand, tossing a lit block into the water and stunning dozens of fish that floated to the surface. The German couple quickly gathered them up. Fishing at that time was not a sport in war-torn Germany, Peterson said. People fished to put a meal on the table. When a horse stumbled into a minefield, people descended on its carcass with knives and quickly stripped it clean. “All the little kids used to come stand by our garbage cans looking for food,” Peterson said, glancing at his own grandchildren. “I would always save them a little bit. They had nothing. We used to get a ration, cigarettes, some gum, a candy bar. I would keep the cigarettes and give them the rest.” It was hard to hate the Germans, he said, because many of the young people they captured had no more desire to be at war than he did. Heinlein, who is making his first visit back to Normandy since D-Day, said he was particularly pleased to see the church steeples have all been rebuilt. American artillery targeted steeples in all the towns they liberated because they were a favorite hiding place for snipers. ••• The day ended in the American cemetery at Colleville sur Mer, an impeccably maintained landscape dotted by white crosses and stars, in view of the beach that more than 2,500 men died trying to take. At first, Peterson said he would not go into the burial grounds, instead wandering past the stone memorial and down to the beach overlook, away from his children. Out of earshot, he described how the bodies were

- 14. collected, tossed onto the back of six-wheel dump trucks to be taken from the beach for burial. Members of the 129th Division's military band drew the distasteful duty. After gazing out at sea for a few minutes, two young Australian tourists asked if he would pose for a photo with them, with the beach as a background. They chatted for a minute, and the men thanked him for his service before heading on their way. Peterson finally wandered into the graveyard portion of the grounds, glancing at the inscriptions for names that he might recognize. “There's probably 150 guys I know buried in here somewhere,” he said. “Are there any names you'd like to look for, Dad?” asked Kris Peterson-Browning, his daughter. “No, I don't think so,” Peterson responded. “One thing for sure, I'm glad you don't have to look for me. It's peaceful here by the water, but I still like it better on Eighth Avenue in Waterford.” r.hamilton@theday.com © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 15. Featured in Military Former Enemies Find Peace On Their Battlefield Published on 6/4/2004 Vierville sur Mer, France Christian Henkes' Uncle was a flight mechanic in the German air force in Paris when Frederick Peterson was storming ashore with the U.S. Army's 29th Infantry Division 60 years ago. On Thursday, they were excited to meet each other at a luncheon for D-Day veterans. Henkes, a reporter for DWTV in Germany, grabbed Peterson for an interview when he found out he was one of the soldiers who came ashore at Dog Green on Omaha Beach, the bloodiest section of the bloodiest beach in the invasion. “These guys fought so hard to liberate Europe — not just France, but all of Europe,” Henkes said. The journalist said he is fascinated by how much has changed in six decades. He knows one German soldier who was a machine-gunner on a fortification at Normandy who has been to the United States eight times at the invitation of the very people he was trying to kill. “I find it amazing that people who faced each other over this beach have come so far that they can now be friends,” Henkes said. “Even with the disagreement over Iraq, Germany is still America's staunchest and most reliable ally in Europe these days.” Henkes said German children are drilled in history in every grade, and the issue of World War II is not sugarcoated — “Everybody is aware that Germany started it.” Peterson, who lives in Waterford, said he is untroubled by the presence of former German soldiers attending the observance this year for the first time, and that an official representative of the German government, Chancellor Gerhardt Schroeder, will be part of the big D-Day ceremony on Sunday for the first time as well. “I think it's good in a way,” Peterson said. “I don't feel any animosity. I'm glad that things are the way they are today. “The war's over, so let's get past it.” Robert A. Hamilton © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 16. Featured in Main Photo 'All Of Us Salute You' D-Day Veterans Earn Thanks, Respect In Normandy Grandcamp, France By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/5/2004 As Frederick A. Peterson got off the bus at the National Guard monument in the Grandcamp city center Friday, a young, athletic- looking man stepped up to the door to offer him a hand. Sgt. Ryan Scott, a member of the 29th Infantry Division, wanted a few minutes with one of the men who forged his division's reputation in World War II. Lester Lease, left, of Baltimore reminisces with Frederick Peterson outside a war “We've come out here for the 60th anniversary of D-Day to listen and museum at Utah Beach on Friday. Both were attached to the 29th Infantry Division to learn while we still can, and to take their stories back to our younger during the invasion. soldiers,” said Scott, who is from Annapolis, Md. “These guys represent an important part of our history.” About 100 soldiers of the 29th, a National Guard unit based in Ft. Belvoir, Va., were chosen to come to France to honor the veterans of the “greatest generation.” Most have recently been chosen as their units' soldiers of the year or non-commissioned officers of the year, or have earned other honors. Peterson and Scott were soon sharing notes about the things that have changed over the decades, and the things that are the same. Peterson recalled his basic training at Fort Belvoir: all hills, forest and Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette snakes. Scott smiled. Glenn Nauman, left, of Pennsylvania, and Joe Heinen of Maryland, both of whom “The woods and the snakes are still there,” he said. “That's the way we served in the 29th Infantry Division, listen to a speaker during a service on Friday like it.” commemorating Frank Peregory, who served with the 29th and was killed in the Peterson also observed that it was raining on June 4, 1944, and that it fighting at Grandcamp, France. was raining when he was in Normandy on June 4, 1994, for the 50th anniversary, and that it was raining off and on again this year. “Maybe the bad weather follows me around,” he said. The 83-year-old has traveled from his home in Waterford to France with nine family members to be among the veterans in this year's commemoration, which culminates in special events Sunday. While the two men talked, a three-star general helped another aging soldier to his seat for an outdoor ceremony. Another officer fetched a water bottle for a veteran artilleryman who had already settled in. Meanwhile, residents and elected leaders of Grandcamp gathered to recognize the Americans. Children clutched their hands and thanked them for freeing France from the dark days of Nazi occupation.

- 17. And so the veterans of the 29th learned that the younger generation, both at home and here, has not forgotten their sacrifices of 60 years ago. “We are gathered here today to remember, to honor these men who came from a far land, to fight, and to die,” said Jean Marc LeFranc, a former mayor who is now a member of the French parliament. “Thank you, thank you from the bottom of our heart for what you did. And you did it so well.” “I think all of today's veterans will agree that the reception they got today is much nicer than the one they got 60 years ago,” said Maj. Gen. Daniel Long, the current commander of the 29th. He noted that one member of the division earned the Medal of Honor for his actions near Grandcamp two days after the invasion began but was killed 10 days later before he knew about the honor. The commemoration, Long said, pays homage to every man who helped to free Europe from Hitler's grasp. “In our minds,” the general said, “they were all heroes.” ••• Friday began with a visit to Utah Beach, which was stormed by the 1st Infantry Division, the Big Red 1. The division suffered far fewer casualties than did the 29th at Omaha Beach on that first day. Peterson walked along the top of the dunes and observed their gentle slopes and the flattening of the land behind them. The layout is in stark contrast to the cliffs and fortifications that faced his 121st Combat Engineer Battalion on Omaha Beach, where the soldiers supported the 116th Infantry Regiment. “I tried to tell the captain we should come ashore here, but he just said, ‘Hey, who's in charge here?' ” Peterson joked. “This was more of a walk-in, according to the guys I talked to. Once the troops were off the boat, all they had to do was run across the beach because there was nothing to stop them.” Nothing, he added, except for artillery barrages, machine guns, tanks and the barbed-wire fences to slow them down so that the German guns could cut them to pieces. The standard way to get a platoon across the wire, Peterson said, was for the first man to jam his rifle into the ground, fold the wire down, then place his body on top of it as the other soldiers ran over his back. “That's what they taught us in training, and it worked,” he said. “It paid to pay attention.” Peterson spotted Lester Lease, a technical sergeant with the 116th Infantry Regiment whom he met at the 50th reunion, when Lease had come from his Baltimore home with his 14-year-old grandson. He hustled over to ask how the boy was doing. The grandson is now an Army helicopter pilot who finished second in his class at officer candidate school and flight school two months ago and will probably head to Iraq before the end of the year, Lease said. Not far from where they chatted, the Germans had ambushed Lease's unit almost 60 years earlier. After 15 hours of marching, the Americans had collapsed in what seemed a secure spot, only to be encircled by the Germans. They were awakened by opening fire. In a few seconds, 129 members of the regiment, more than a quarter of its remaining strength, were killed or captured. Peterson compared remembrances of his own unit's ambush at about the same time and a few miles away. He had been away on reconnaissance but returned to find the troops under heavy fire. By the time the battle was over, only about 35 of 200 men who had stormed ashore were still standing. ••• At one point, the caravan of five tour buses carrying the veterans and their families passed through St. Lo, site

- 18. of a fierce battle when the 29th advanced from the beaches. The 116th's commander, a major, had told his men that if he died in the attempt to take the town, he wanted them to lay his body on the steps of the church. “That was his objective, to take that town even if it killed him,” Peterson recalled. “And he did, and it did, and they laid his body on the steps of the church.” The day ended in the town of Isigny, which the 29th freed from the Germans on June 9, linking the beachheads established at Utah and Omaha. More than 50 re-enactors in uniforms that were true to what soldiers of the 29th wore on D-Day stood at attention as an honor guard when the veterans entered the town square. Hundreds of city residents lined the park's borders, and the American flag was raised on the tallest pole, generally reserved for the French colors. Mayor N. Queonel Gerard observed that the children still learn in their history lessons what the 29th did for Isigny. He said that photographs in the town hall document the end of the German occupation. “Liberty is a very precious thing, and very often it has to be obtained by very tough fighting,” Gerard said. “Our role as citizens is to preserve it.” The townspeople placed several large floral wreaths at the base of a new monument, fitted with a brass plaque that reads in part: “The people of France and the United States will always share a love of liberty, and the sacrifices and triumphs of our citizens in 1944 will bind our two countries together forever.” Gen. Long, who spoke briefly at the Isigny ceremony as well, said he appreciated so many children taking part. “I hope they never have to go through what these men went through,” he said. Don Miller, a veteran of the 29th's 175th Infantry Regiment, said the soldiers had stopped at the city's edge, worried that the Germans had mined a dam above it and would flood Isigny if they entered. Their commanding general urged them on, and they were dismayed to find the city in flames because of the bombs and artillery strikes intended to dislodge the enemy. He said it was gratifying to return to a rebuilt city with much of its historic charm. “All of us salute you,” Miller said. “Thank you for inviting us back, one more time.” © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 19. Featured in Main Photo Pictures To Go With His Words For Veteran's Family, D-Day Stories Come To Life St. Clair Sur Elle, France By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/6/2004 For a decade Frederick A. Peterson's son Vaughn has traced the 29th Infantry Division's path through France, Belgium and Germany, so he was familiar with the terrain, in theory. His father, who is 83 and lives in Waterford, was with the 29th from the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, through the end of the war. Following his father on a tour organized by the 29th Division Association for the Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette last five days has given Vaughn Peterson a much greater appreciation Frederick Peterson, right of the flag in of what his father experienced. foreground, listens quietly to a speaker with other members of the 29th Infantry Division “Seeing the names on a map, and then being here, it's almost like and their families during a memorial ceremony at St. Clair Sur Elle on Saturday. being transported back to that time, just without the horror,” said the younger Peterson, who is 57. “I can just picture dad sitting in his Jeep right over here in one of these fields, or hunkered down with his rifle and cracking off a few shots at the Germans from behind a hedgerow. I can just see it.” Marlene Lord, the senior Peterson's daughter, said seeing the monuments to the 29th and watching how her father is treated with deference by residents of the small towns they pass through on the tour has given her a new perspective on him. As a girl growing up, she thought of him as a father and Pfizer researcher. Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette “I'm so proud of him,” she said. “He's always been just dad, and we Kenny Cooke, right, a D-Day veteran from heard about his experiences to a limited degree, but we always had to Oregon and a member of the 121st Combat Engineers, shares a laugh with Frederick ask him for the stories. But to be here and see the people and the way Peterson as he shows him a WWII era they feel about him, it makes it that much more real. ... photo of the two of them with two other comrades. “Then you hear about how they were supposed to be in St. Lo in six days, and how it took 45 days to get there, and you realize a little bit what it must have been like.” Lord, who lives in East Lyme, is one of several family members who traveled to France with her father for the 60th anniversary commemoration of D-Day. Everywhere the veterans' tour buses have traveled, townspeople have leaned out of windows to wave and take photographs. Many have bedecked their houses with American flags and other decorations. In one car repair shop the mechanics stopped their work on a brake job to come outside and wave, as did an elderly woman who looked barely strong enough to lift her arm. Lord noticed another sign of the respect: at a brief reception in St. Clair sur Elle, the wine was served in crystal glasses, not plastic, to several hundred 29ers and villagers.

- 20. “You probably wouldn't find that in the U.S. for a huge gathering of people like this,” she said. “The whole town really went all out to pay honor to these veterans.” The tour on Saturday also passed through the towns of St. Jean de Savigny, St. Marguerite d'Elle and Le Carrefour, concluding with a cocktail party at Chateau Canisy, where the veterans and their families were entertained by the University of Wisconsin Choir. “It's mostly the route that we followed 60 years ago,” said Peterson. “Then we swung north and joined the Ninth Army, and headed for the North Sea. We didn't stop until we were in Germany.” Today the towns are picturesque, with rural French architecture, and each has its particular beauty and charm. When 29th came through during the war, Peterson said, the towns all looked the same because of the damage caused by the retreating German forces and the advancing Allies. “Dad always said it was tough to distinguish one from the next, because they were all rubble,” Vaughn Peterson said. ••• The last time Peterson saw James K. Cooke, they were fighting their way through Germany. Though it's been nearly 60 years, he still recognized “Cookie” on Saturday when they ran into each other in a gymnasium in the small riverside town of St. Clair sur Elle. “Hey, Cookie, remember me?” Peterson asked. When Cooke answered with only a puzzled gaze, Peterson pulled out a black-and-white snapshot of four soldiers preparing to lay a minefield, taken not long after they came ashore at Omaha Beach just after dawn on June 6. Peterson was second from the right, Cooke on the far left. “You growed up,” Cooke said in mock amazement as he looked up at Peterson. “Good to see you, Cookie, good to see you,” Peterson said, as the men started to exchange war stories. Cooke, who lives in Merlin, Ore., was a staple in the few stories Peterson would tell his children when they were growing up. He told them how “Cookie” was in a truck traveling down a dirt road in France when it hit a mine, blowing dirt in his eyes. “Dirt in his eye,” the Peterson family has since learned, was a euphemism for blast bits that nearly robbed Cooke of his eyesight. Peterson, who had been in a Jeep ahead of the truck, miraculously missed the mine. “I wound up in the hospital for three days,” Cooke recalled. “Those medics were pretty good. They treated my eyes and wrapped my whole head up in bandages. And when they took them off three days later, the fog started to clear and I could see again.” Cooke was supposed to have bed rest, but he would hear none of it. “I don't like hospitals much,” he said, “so I went AWOL and got back to my unit.” Peterson's family has also heard the story about the unit that blew up a wall at Vierville so that tanks and trucks could drive off the beach. And for the first time since the war, in a theater in St. Marguerite d'Elle where the 29th veterans stopped for lunch, Peterson saw Walter Condon, who now lives in Shrewsbury, Mass., and was part of the detail that destroyed the wall. What Peterson had not told his family was that the combat engineer team that did the job was the only one of

- 21. three teams – each armed with a half-ton of high explosives and a bulldozer – to make it through the withering fire from German machine guns, artillery and snipers. “We landed at 7 in the morning, and we didn't get to that wall until 5 o'clock at night,” Condon said. “But by 5:15 we blew that wall, and anything that could move got off the beach pretty quick.” One of Peterson's grandsons, Alex Lord, listened intently to the remembrances. “We all have a copy of that picture with Cookie, and we've all heard the stories,” he said. “But it was amazing to see him talking with those other veterans. It really brings the stories to life.” ••• Most of Saturday was spent at brief ceremonies at roadside monuments that have been erected in honor of the 29th Division throughout this part of Normandy. In a ceremony at St. Clair, Mayor Maryvonne Raimbeault noted that there are still artillery shells buried in the walls of the local church and bullet holes in some of the homes. She said barbed wire still circles some of the fields and people use spent shell casings as decorations. “This crossroad was the site of particularly violent combat,” Raimbeault said. “We must remember that our liberation was not an easy campaign for you.” More than 30 men of the village, all taken prisoner by the Germans when they invaded France four years before D-Day, held flags for the 29th veterans. Schoolchildren passed out clay plaques, manufactured by a local company and inscribed with the 29th's symbol. “We will not forget your country and the sacrifices you all made for France to once again be truly free,” the mayor said. “The liberation permitted the people of France to rediscover their roots, their culture, their individual and collective dignity. We're proud of the soldiers from so far away, soldiers who sacrificed their lives for our freedom.” Bryan Walker, a historian who co-founded the D-Day Normandy Veterans of North Central Florida eight years ago, unveiled a flag that he designed and sewed by hand. It features troops of the 29th Division coming off a landing craft into the surf. “It's my tribute to these guys,” said Walker, who for 20 years helped to care for an uncle who had been traumatized by his experiences in D-Day. As one French veteran with a chest full of medals hung back from the crowd, Sgt. Darryl Ingram, a member of the modern 29th Infantry Division's 158th Cavalry, coaxed him to pose for a photograph. The National Guard sergeant drew a smile from the elderly man when he gave him a thumb-up. “There's some type of bond that service people have with one another,” said Ingram, a New Rochelle, N.Y. resident who is one of 100 soldiers from the current 29th following the tour. Sgt. Cory Reynolds, of Martinsville, Va., and a member of the 246th Field Artillery Battalion, agreed. “Everybody here kind of speaks the same language,” he said, patting the division insignia on his shoulder.••• At St. Jean De Savigny, the veterans dedicated several plaques to 29ers, some living, some dead. For Dr. Elmer N. Carter, who was killed serving as a captain with the Medical Detachment, 1st Battalion, 115th Infantry, a passage from one of his own letters home serves as his tribute. “I requested a transfer to a combat battalion and am its surgeon,” he wrote. “It is rough as hell, and I'll admit I

- 22. fear for the future. However, I'm happier here than anywhere else in the Army. ... I don't fear death per se, but it really depresses me to think that I may never see (my family) again.” Carter, who was awarded the Silver Star, Bronze Star and Purple Heart, was killed attending to wounded soldiers 11 days after the invasion at Bois de Bretel. The mayor of St. Jean de Savigny, Daniel Morourd, said the memorial wall was created by students at the University of Building at Caen. They worked three months shaping the stones and made the wall 75 feet long and 5 feet high. “I know I speak for everyone when I say you will always be welcome in our country,” Morourd said. © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 23. Featured in Military ‘You Will Be Honored Ever And Always' Bush, Chirac Pay Tribute To Veterans Of Great Invasion By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/7/2004 Colleville sur Mer, France -- On the 60TH anniversary of the D-Day invasion, President Bush credited the bravery of men like John Pender Jr. A technician 5th class, Pender was gravely wounded as he left his landing craft to head ashore, but he kept going until he had delivered radio gear to his unit. And he did not stop there, Bush said. Pender waded back into the surf three more times to get equipment, continuing his duty until he was shot twice more and fell dead on the beach below the cemetery where Sunday's commemorative ceremony took place. “The ranks of the Allied Expeditionary Forces were filled with men who did a specific, assigned task, from clearing mines, to unloading boats, to scaling cliffs, whatever the danger, whatever the cost. “Americans wanted to fight and win and go home,” Bush said. “Our GIs had a saying: ‘The road home is through Berlin.' History will always record where that road began. It began here, with the first footprints on the beaches of Normandy.” Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette It was a strange twist of fate that brought soldiers from the streets of D-Day veterans Frederick A. Peterson of every state – from California to Connecticut – all the way to France to Waterford, right, and James Rice of defeat an evil that had spread across Europe, the president said, but California, left, reminisce as Rice's son, “those young men did it.” U.S. Navy MA1 Tom Rice, listens following commemorative ceremonies in the U.S. Cemetery at St. Laurant in Colleville sur Then, fixing his gaze on the veterans seated near the podium, Bush Mer, France, on Sunday. told them, “You did it. ... I want each of you to understand you will be honored ever and always by the country you served and the nations you freed.” Frederick A. Peterson, now 83 and a resident of Waterford, was seated less than 75 feet from the president as he spoke. The veteran had a seat he'd paid dearly for 60 years ago as a member of the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion, 29th Infantry Division, one of the men clearing the mines in the invasion of Normandy. “I thought he did a good job,” Peterson said of the Bush speech as the Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette ceremony broke up. “He didn't make anything up, that's for sure.” Guests, dignitaries and former soldiers line the seawall overlooking the English Channel during commemorative The president's description of the rivers of blood and the screams of ceremonies at the U.S. Cemetery at St. the dying, said Peterson, made him cry. He recalled just one of his Laurant in Colleville sur Mer, France, on experiences as a young sergeant on Omaha Beach: “There was a guy Sunday.

- 24. not five feet from me yelling for help, and nothing I could do about it.” Sgt. 1st Class George Carter, on active duty with the 29th Infantry Division today, started Sunday with a brief ceremony at H-Hour, 6:30 a.m., on the same beach where the 29th and the 1st Infantry Division came ashore 60 years earlier. “As a soldier, you see 300 yards of flat sand and nothing to hide behind. It puts the fear of God into you, I'll tell you,” Carter said. “And there's another wave of men coming in behind you, so you can't stay there, you have to move forward.” Bruce M. Wright, now living in Old Saybrook, was in law school when he was drafted, and he waded ashore on D-Day as part of the 1st Infantry Division. After the war, he returned to law school and later became a judge on the New York Supreme Court. “It was almost a mathematical procedure how things had been plotted out in advance,” Wright said. Despite the heavy losses, he said, conditions could have been far worse without that planning. “At the outset, the Germans thought they could wipe us all out, and they certainly sprinkled us all with small arms fire,” he said. “But they had their backs to us most of the rest of the war.” Buy this Photo Suzanne Ouellette Wright was wounded by shrapnel twice during the drive through Waterford resident Frederick Peterson France and into Germany. Hit in the neck and then in the leg, he was walks through the United States military treated both times in the field and then returned to his unit. cemetery at St. Laurant Sunday after activities commemorating the 60th anniversary of the D-Day invasion of Though Bush got a standing ovation at the end of his 18-minute Normandy in Colleville, France. address, Wright said he thought the president was disingenuous. “Our president never commanded anything in wartime,” he said. ••• Peterson and other veterans participating most of last week in the D-Day tour organized by the 29th Infantry Division Association have been setting a tough pace. Typically they have started every day by 8 a.m. and returned to their hotels by 8 p.m. Sunday was even tougher. The aging men got up before 4 a.m. to get ready to go through all the security checkpoints set up around the cemetery where the major commemorative ceremony took place. “They're made of tough stuff,” said Alex Lord, Peterson's grandson. “They had to be to do what they did.” The ceremony was at Normandy American Cemetery, a bit of sovereign American soil where the bodies of 9,387 Americans are buried under simple, white marble crosses or stars. The names of 1,157 more troops whose bodies were never recovered or identified are listed on a Wall of Honor. When the cemetery gates were opened hours before the 9:30 a.m. start to the commemoration, veterans began to stream in. Each of the graves had two fresh flags, one of the United States and one of France. The cemetery was the scene of the opening and closing scenes of the film “Saving Private Ryan.” On Sunday, Matt Damon, the actor who played Pvt. James T. Ryan, circulated through the crowds. Actor Tom Hanks, who played the lieutenant trying to rescue Ryan, and director Steven Spielberg, who made the movie, also attended.

- 25. People jockeyed for position to get a memento of some of the dignitaries in attendance. Peterson's grandson, 11-year-old Trevor Browning of Norwich, was given charge of the family camera for a bit. “Do you want two pictures of President Bush or just one, Mommy?” Trevor asked. “I want to take a picture of Jacques Chirac – Jacques Chirac, right, Mommy?” “Yes, he's the French president,” Kris Peterson-Browning answered. “How come they don't have a king?” Trevor shot back. Members of Congress were scattered throughout the crowd of veterans, who got the seats up front. U.S. Rep. John Larson, D-1st District, and his wife Leslie, were among them. “These people are the whole reason we're here,” Larson said. “Sitting up there and listening to their stories meant so much to me,” Leslie Larson said. “So much more than it would have meant sitting anywhere else.” ••• The ceremony began with a rendering of honors to the veterans and a 21-gun salute using artillery by the water's edge. As the guns fired, flames and clouds of white smoke billowed into the air. The veterans barely flinched, though some in the crowd ducked at the first blast. As four A-10 Warthogs passed overhead, one of the planes peeled off in a “missing man” formation, disappearing upward into the bright morning sun. Chirac spoke for about five minutes, in French. The veterans had been issued radio receivers and headphones that allowed them to listen to the address in English. Bush noted that one American unit lost nine out of 10 men who went ashore. A British commando unit lost half its men. By the end of June 6, 1944, and despite the enormous losses, the Allies had 100,000 troops ashore. They had cracked the myth of Hitler's “Fortress Europe” and begun their liberation of occupied France. The Nazis threatened execution of anyone caught cooperating with the invasion forces, but people nonetheless subverted the Germans whenever they could, Bush said. He told of a little girl in Amsterdam who hid in an attic and listened to news of the invasion on a radio. “She wrote in her diary, ‘It still seems too wonderful, too much like a fairy tale,' ” Bush recounted. The liberation of Europe came at a terrible cost, the president said. He noted the words of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who said that it was a terrible thing that the men who died on D-Day would never have grandchildren, then he thanked God that his own grandchildren would grow up in freedom because of those men's sacrifice. Bush described the beach as the sun rose on June 7, 1944. Scattered across the sand were rifles, canteens, K- rations and other belongings of the men who had fallen, as well as Bibles they had dropped. “Our boys had carried in their pockets the book that brought into this world the message, ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends,' ” Bush said. “America honors all the liberators who fought here in the noblest of causes. And America would do it again for our friends. “We pray in the peace of this cemetery that they have reached the far shore of God's mercy. And we still look with pride on the men of D-Day, and on those who served and moved on.”

- 26. Featured in Military Lieutenants Were The Unlucky Ones By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/7/2004 Colleville sur Mer -- Frederick Peterson was a platoon leader with the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion when he turned down a battlefield commission. He figured the promotion to an officer and the extra pay weren't worth the risk. In less than a year, during a time when he was the top enlisted person in his platoon, five lieutenants in his unit were wounded or killed. The changeover in officers was so fast he can't recall most of their names. There was one brash man, Peterson said, who showed up weeks after the invasion started and admonished the men, “You guys think you've seen combat? I'll show you combat.” “I don't think he lasted more than a few days,” Peterson said. “Before you knew it, he was on his way home on a stretcher.” Another lieutenant was killed on the beach by a shell from one of the Navy ships that fell short of its German target. A third was killed by German artillery. Despite the unit's reputation for losing lieutenants, Peterson said, nobody from the outside ever seemed reluctant to take command. Peterson felt differently. “I figured, if you're a lieutenant, you've got to stay out in front and say, ‘Let's go men,' rather than stay with the platoon and say, ‘Get going, men,' ” he said with a laugh. On a more serious note, Peterson added, “Why be a lieutenant? I knew I was going to leave the service as soon as the war was over. I didn't want a career.” © The Day Publishing Co., 2004

- 27. Featured in Military There Were Rabbits And Hillbilly Songs By ROBERT A. HAMILTON Day Staff Writer, Navy/Defense/Electric Boat Published on 6/7/2004 Vire, France -- When the 121st Engineer Combat Battalion arrived in England in 1942, a young man from the hill country down South who loved rabbit meat quickly determined that the chalky soil near Tidworth was filled with the animals. He had an unusual method of hunting them, recalled Frederick Peterson, a D-Day veteran from Waterford who was a platoon sergeant with the 121st. “He would stand over a rabbit hole and wait. He'd wait so long, the rabbit would stick his head out and he'd hit it with a club. He'd come back to the camp with about five rabbits in his belt. “We had a bunch of characters in our company, didn't we?” Peterson recalled on Sunday as he chatted with James K. Cooke, a fellow veteran from Merlin, Ore. Peterson said he hasn't thought about a lot of men in his platoon for years. “But you see these guys, and you start talking, and things click.” Peterson remembered a Tennessee soldier, a fearless man by the name of Phelps who could neither read nor write. So another soldier, Lewis Harrower, known as “Upstate Harry” because he came from upstate New York, would read Phelps' letters to him and then write his letters to send back home. And then there was Poteet – Peterson can't recall his full name – who scrounged up a guitar soon after the D- Day invasion and entertained everybody with a song about “sitting on a log, hand on the trigger and an eye on the hog,” and another one about “saying his prayers to the hens upstairs.” “You'd find things here and there,” Peterson said. “I don't know where he found it, but he found it, and he was always playing these hillbilly songs.” Peterson recalled a guy who used to throw packs of cigarettes up into the air and shoot at them for pistol practice. “A pack of cigarettes probably cost about a quarter back then,” Peterson said. “Now it would cost you $5 for each target.” One of the greatest characters in the unit, Peterson added, was Cooke himself, known as Cookie back then. Returning after one reconnaissance, Cooke came back with 20 German prisoners. “I'd just gone over a hedgerow into a field, and there was a cavalry outfit,” Cooke said. “It was easy, because they were tired and they wanted to give up. I just told them to follow me. But I'll tell you, it scared the hell out of me there for a minute.” The troops were armed, he said, “but they never pulled them on me.” Instead, he gathered up their weapons and later shipped nine German Lugars back to friends and family at home. The Germans were sent to a prison camp.