UK Adjudicators February 2022 Newsletter

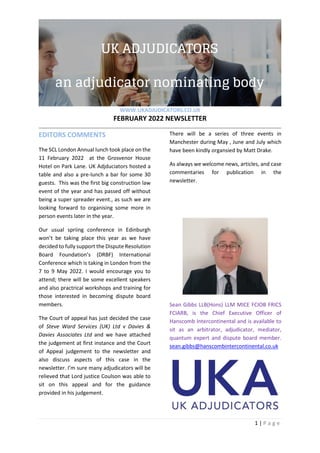

- 1. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 1 | P a g e EDITORS COMMENTS The SCL London Annual lunch took place on the 11 February 2022 at the Grosvenor House Hotel on Park Lane. UK Adjduciators hosted a table and also a pre-lunch a bar for some 30 guests. This was the first big construction law event of the year and has passed off without being a super spreader event., as such we are looking forward to organising some more in person events later in the year. Our usual spriing conference in Edinburgh won’t be taking place this year as we have decided to fully support the Dispute Resolution Board Foundation’s (DRBF) International Conference which is taking in London from the 7 to 9 May 2022. I would encourage you to attend; there will be some excellent speakers and also practrical workshops and training for those interested in becoming dispute board members. The Court of appeal has just decided the case of Steve Ward Services (UK) Ltd v Davies & Davies Associates Ltd and we have attached the judgement at first instance and the Court of Appeal judgement to the newsletter and also discuss aspects of this case in the newsletter. I’m sure many adjudicators will be relieved that Lord justice Coulson was able to sit on this appeal and for the guidance provided in his judgement. There will be a series of three events in Manchester during May , June and July which have been kindly organsied by Matt Drake. As always we welcome news, articles, and case commentaries for publication in the newsletter. Sean Gibbs LLB(Hons) LLM MICE FCIOB FRICS FCIARB, is the Chief Executive Officer of Hanscomb Intercontinental and is available to sit as an arbitrator, adjudicator, mediator, quantum expert and dispute board member. sean.gibbs@hanscombintercontinental.co.uk

- 2. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 2 | P a g e DISPUTE BOARD MEMBER ACCREDITATION FIDIC have successfully accredited dispute board members on their new assessment courses. The course though does not offer training; it assesses qualified dispute adjudicators who offer dispute avoidance and/or dispute adjudication services to the infrastructure industry. Candidates are tested on: • Knowledge of FIDIC Contracts, including all main FIDIC publications providing for Dispute Boards or Adjudication, the FIDIC Golden Principles and also multi-lateral development banks specific requirements • Contract/construction law principles under common and civil law jurisdictions • Evidence law and procedures • Dispute Board (DB) good practice and procedures • Ethical standards • Technical matters, delay analysis and the evaluation of quantum for both variations and time related costs and basic financial knowledge of VAT, bank guarantees etc. • Decision making and Award writing skills • Ability to manage and control a meeting, hearing or site visit • Time Management • Interpersonal skills FIDIC Contracts for the assessments include: 1. Conditions of Contract for Construction for Building and Engineering Works Designed by the Employer (Red Book), first edition, 1999 2. Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design Build for Electrical and Mechanical Plant, and for Building and Engineering Works Designed by the Contractor (Yellow Book), first edition, 1999 3. Conditions of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects (Silver Book), first edition, 1999 4. Conditions of Contract for Construction for Building and Engineering Works Designed by the Employer, MDB Harmonised Edition, June 2010. 5. Conditions of Contract for Construction (Red Book), second edition, 2017

- 3. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 3 | P a g e 6. Conditions of Contract for Plant and Design Build (Yellow Book), second edition, 2017 7. Conditions of Contract for EPC/Turnkey Projects (Silver Book), second edition, 2017 8. Conditions of Contract for Underground Works (Emerald Book), first edition, 2019 9. FIDIC Golden Principles (2019), first edition. 10. The Short Form of Contract (Green Book) first edition, 1999 11. Conditions of Contract for Design, Build and Operate Project (Gold Book) first edition, 2008 12. Conditions of Subcontract for Construction For building and engineering works designed by the Employer, first edition, 2011 13. Form of Contract for Dredging and Reclamation Works, second edition, 2016 14. Client/Consultant Model Services Agreement (White Book), fifth edition, 2017 15. Sub-consultancy agreement, second edition, 2017 16. Conditions of Subcontract for Plant and Design Build, first edition, 2019 A significant number of Dispute Board Panel Members on the UK Adjudicators international panel have undertaken this accreditation and are also listed on the FIDIC President’s List of Adjudicators and Mediators. https://www.ukadjudicators.co.uk/dispute- board To find out more about accreditation and assessment do look at the website: https://fcl.fidic.org/our- programmes/adjudicators/ To find out more about the FIDIC President’s List of Adjudicators and Mediators do look at the website: https://fidic.org/president-list

- 4. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 4 | P a g e IS AN ADJUDICATION DECISION ENFORCEABLE EVEN WHEN IT IS INCORRECT IN SOUTH AFRICA? Is an Adjudication decision enforceable even when it is incorrect? The South Africa Supreme Court of Appeal has recently shed light on whether an adjudicator’s award is binding on both parties in the case of Framatome v Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd ((355 of 2021) [2021] ZASCA 132 (01 October 2021)). The Case The contract between Eskom and Framatome is that they used a NEC 3 contract for the replacement of steam generators at Koeberg Nuclear Power Station. This contract, being a NEC contract, provided for adjudication as the first method of dispute resolution between the parties. There was a despite that arose relating to a compensation event notified by the project manager of Eskom. Framatome won this dispute when it came to adjudication and Eskom ignored the adjudicator’s award. Another dispute went to adjudication which dealt with the assessment of the compensation event of the original dispute. Eskom refused to provide an evaluation of the compensation event and the adjudicator concluded that Eskom had failed to make a full assessment in due time as required by the original decision. Framatome’s proposed quotation was concluded to be accepted in terms of the provisions of the contract.

- 5. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 5 | P a g e Eskom notified the adjudicator of its dissatisfaction with this decision and Framatome tried enforcing the various decisions in the High Court. The High Court found in favour of Eskom that the adjudicator had acted outside his terms of reference and that he exceeded his jurisdiction. He had decided on issues not referred to him. Framatome appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeal. Court of Appeal Decision The court asked the question of whether or not the adjudicator confined himself to a decision of the issues that were referred to him by the parties. If he did so, then the parties were bound by his decision. The court held that: a) The adjudicator did confine himself to the issues referred. At no point did he depart from the real dispute between Eskom and Framatome. b) Only an arbitral tribunal could revise the adjudicator’s decision – because an arbitral tribunal had not been used, the decision was binding on both parties. c) Eskom was ordered to make full payment to Framatome. The court remained in line with Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts, that ‘it is only in rare circumstances that the court will interfere with the decision of an Adjudicator…’ The usual position that an Adjudicator’s decision can only be interfered with where there the adjudicator has no jurisdiction, where there is really bias, or the appearance of bias still applies. A party should not agree to refer a dispute to adjudication assuming that if the adjudicator decides against them, they can ignore the decision. The courts still will promote the idea that an Adjudicator’s decision will be enforced in the majority of cases. https://lawlibrary.org.za/za/judgment/supre me-court-appeal-south-africa/2021/132 George William Gibbs – LLB (Hons) LPC Consultant, Hanscomb Intercontinental Ltd

- 6. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 6 | P a g e BRAVEJOIN COMPANY LTD V PROSPERITY MOSELEY STREET LTD [2021] EWHC 3598 (TCC) (13 DECEMBER 2021) INDEMINITY COSTS The TCC has once again firmly shown its support for adjudication by awarding indemnity costs against the defendant that tried to resist the enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision. The case itself isn’t very interesting and can be summarised briefly; the Technology and Construction Court (TCC) rejected an argument that there was no crystallised dispute capable of reference to adjudication, in a case where the defendant argued that there was no contract between it and the claimant. The adjudication concerned the claimant’s right to payment for construction works, and the TCC considered that the defendant’s ‘no contract’ argument was a denial of liability to make payment, therefore indicating the existence of a crystallised dispute. The TCC’s robust approach to enforcing adjudicator’s decisions is the reason adjudication has worked so well in the United Kingdom and must be applauded. The sanction of indemnity costs will deter most parties from raising spurious challenges to a decision. BILTON & JOHNSON (BUILDING) CO LTD V THREE RIVERS PROPERTY INVESTMENTS LT [2022] EWHC 53 (TCC) (14 JANUARY 2022) The Technology and Construction Court (TCC) dismissed two challenges to the enforceability of an adjudicator’s decision, based on alleged breaches of natural justice. It found that the adjudicator had been entitled to reach a view on which contractual terms applied to the dispute without adopting the precise arguments made by either party, and that he had not failed to determine a rectification defence raised by the employer. JOHN GRAHAM CONSTRUCTION LTD V TECNICAS REUNIDAS UK LTD [2022] EWHC 155 (TCC) (27 JANUARY 2022) Chris Ennis was the fourth adjudicator in a series of adjudications and had to determine the true value of an interim application for payment. The sum awarded included £355,000-odd that the defendant disputed was due. It maintained it could contra charge for a replacement sub-contractor to complete the claimant's works and paid only part of the adjudicator's decision having validly terminated. The defendant wouldn’t comply with the decisions and the claimant

- 7. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 7 | P a g e commenced proceedings to recover the balance. In enforcement the defendant argued that the adjudicator had acted in excess of or outside his jurisdiction. It said it had not waived its right to raise this jurisdictional challenge, arguing that the jurisdictional error was so fundamental and not capable of being waived, and it did not have actual or constructive knowledge of the error until the adjudicator's decision was issued. The jurisdictional error was said to arise because, in a decision dated March 2019, the first adjudicator determined the scope of the sub-contract works and the claimant subsequently refused to undertake works outside that scope. That matter was referred to arbitration and in the first award (dated June 2020), the adjudicator's decision on scope was overruled. The fourth adjudicator agreed that the parties were required to comply with the first adjudicator's decision until June 2020, and that legitimised the claimant's refusal to carry out works and meant the defendant could not levy the contra charge. The defendant said this showed the fourth adjudicator refused to give effect to the arbitration award and gave continuing effect to the first adjudicator's decision. The judge disagreed with the defendant and enforced the balance of the adjudicator's decision. He held the fourth adjudicator expressly acknowledged that he was bound by the arbitration award. Further, he did not answer the wrong question. He decided the defendant could not levy the contra charge because the loss flowed from complying with the first adjudicator's decision, not the claimant's breach of contract. It was immaterial whether that was right or wrong. Obiter, he held that the defendant did not have actual or constructive knowledge of this jurisdictional objection prior to the adjudicator's decision, so it had not waived its rights to challenge on this basis. Although the judgment neatly summarises the principles of adjudication enforcement, the really interesting aspect is the interplay between adjudicators' decisions (which are temporarily binding) and arbitration awards (which have finality), and how subsequent adjudicators have to tread carefully between the two.

- 8. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 8 | P a g e STEVE WARD SERVICES (UK) LTD V DAVIES & DAVIES ASSOCIATES LTD [2022] EWCA CIV 153 (14 FEBRUARY 2022) On appeal from DAVIES & DAVIES ASSOCIATES LTD V STEVE WARD SERVICES (UK) LTD [2021] EWHC 1337 (TCC) (19 MAY 2021) At first instance Roger ter Haar QC gave summary judgment to enforce payment of an adjudicator's fee arising from an adjudication in which the adjudicator resigned prior to issuing a decision. The adjudicator was appointed under the CIC's Low Value Disputes Model Adjudication Procedure (LVD MAP) and the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998 (SI 1998/649) applied, but the adjudicator also provided his terms and conditions of appointment. The terms required payment even if no decision was issued. Before issuing a decision, the adjudicator concluded he lacked jurisdiction because the adjudication had been started against the wrong responding party. He resigned and claimed his fees from the referring party who became the defendant in the court hearing. The defendant refused to pay so the adjudicator sued for his fees and applied for summary judgment, which the court granted. Roger ter Haar QC made a number of interesting findings. While the adjudicator could take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and law (including who the parties to the contract were), in circumstances where neither party had raised a jurisdictional point, "it would have been wiser" for the adjudicator to raise the matter with them. He had relied on the power in paragraph 13 of the Scheme, but this was outside the ambit of that power and his reasoning was erroneous. That said, he acted in accordance with what he considered was his duty to the parties and there was no breach of his terms of engagement, since paragraph 9(1) of the Scheme allows the adjudicator to resign at any time. Further, the adjudicator could rely on his terms and conditions, there was no bad faith and the clause satisfied the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (UCTA) reasonableness test. The Defendant didn’t like the decision and appealed, the appeal being heard by three judges, one of which was Lord Justice Coulson. Lord Justice Coulson delivered the judgement of the court and in the judgement identified six issued that the court needed to answer.

- 9. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 9 | P a g e a) Issue 1: Was there a jurisdictional issue in the adjudication? There a real jurisdictional issue in this case which Mr Davies was obliged to address. b) Issue 2: Was Mr Davies entitled to decline jurisdiction and resign in consequence? The adjudicator was entitled to decline jurisdiction pursuant to paragraph 13 of the Scheme, he had reasonable cause to resign in all the circumstances of this case. c) Issue 3: Subject to bad faith, was Mr Davies entitled to be paid for the work done prior to his resignation ? The adjudicator was entitled to be paid for the work done prior to resignation. d) Issue 4: Was Mr Davies guilty of bad faith? The adjudicator was not guilty of default/misconduct, much less bad faith. e) Issue 5: Were Mr Davies' own terms of appointment contrary to UCTA? The adjudicators terms were not contrary to UCTA, UCTA had no application to the present case. f) Issue 6: Should this court interfere with the judge's costs order? The court shouldn’t interfere with the judge's costs order. The adjudicator charged an hourly rate of £325.00 plus VAT for his time on the adjudication and through the various court hearings. The court had no objection to this rate and awarded costs based on the application of this rate. The adjudicator confirmed this rate in his terms and conditions, the court approved the adjudicator doing this and it would be advisable for others sitting as adjudicators to always do this. The wording was : Basis of Charge Time related for hours expended working or travelling in connection with the Adjudication including all time up to settlement of any Fee Invoice, which, for the avoidance of doubt, may include any time including Court time, spent securing payment of any fees, expenses and disbursements due.

- 10. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 10 | P a g e Aspects of the law were restated in the judgement which parties, party representatives as well as adjudicators should take note of. ‘An adjudicator has no jurisdiction if it is arguable that there is no contract at all (see Dacy Building Services v IDM Properties [2017] BLR 114; M Hart Construction v Ideal Response Group (2018) 117 Con LR 228), or where there is a non-qualifying construction contract: see The Project Consultancy Group v The Trustees of the Gray Trust [1999] BLR 377. If a defendant can demonstrate a reasonably arguable case that either he or the claimant were not a party to the construction contract, the adjudicator has no jurisdiction to make any decision, and it will not be enforced against him: see Thomas-Frederic’s (Construction) Limited v Keith Wilson [2003] EWCA Civ 1494; [2004] BLR 23. There have been a number of subsequent cases in which an adjudicator’s decision was not enforced because of doubts as to the proper parties to the contract: for a case where the claimant was arguably not a party to the construction contract so the decision was not enforced, see ROK Build Limited v Harris Wolf Developments Co. Limited [2006] EWHC 3573 (TCC)); for a case where the defendant was arguably not a party to the construction contract so the decision was not enforced, see Estor Limited v Multifit (UK) Limited [2009] EWHC 2108 (TCC); [2009] 126 Con LR 40.) As this court acknowledged in Thomas- Frederic’s, a defendant who has agreed to be bound by the adjudicator’s decision will not be able to resist enforcement, even if that defendant was not a party to the contract. Whether or not the defendant has agreed will depend on the evidence, in particular as to whether the defendant had reserved its position in respect of jurisdiction (see Thomas-Frederic’s and Brims v A2M [2013] EWHC 3262 (TCC) at [33]), or had otherwise waived any such objection (see Aedifice Partnership Ltd v Shah [2010] EWHC 2106 (TCC); [2010] CILL 2905 at paragraph 21(e)). If two parties have unequivocally agreed to adjudication, even if one of them is not a party to the construction contract, then they have agreed to ad-hoc adjudication and the resulting decision can be enforced: see, by way of example, the decision in Nordot Engineering Services Ltd v Siemens PLC (SF00901 TCC16/00) dated 14 April 2000; CILL September 2001, approved in Thomas- Frederic’s. Under paragraph 13 of the Scheme, the adjudicator has to investigate the matters “necessary to determine the dispute”. If an

- 11. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 11 | P a g e adjudicator considers that it is necessary to work out if he or she has the jurisdiction to determine the dispute in the first place, then they are duty bound to consider and determine that issue. That in turn means that they should raise that issue with the parties before coming to their own conclusion. In Primus Build Ltd v Pompey Centre Ltd and another [2009] EWHC 1487 (TCC); [2009] BLR 437, the adjudicator spotted a point of significance (in that case, various figures in one party’s accounts, rather than a potentially fatal jurisdiction issue) which neither party had addressed. Although it was not disputed that the adjudicator was entitled to consider those figures, the court found that fairness required him to raise the point with the parties before reaching a decision based on those figures. In my view, Paragraph 13 of the Scheme gave Mr Davies the express power to do just that: to consider and raise with the parties a point which they had not raised but which he thought was important. There is no binding authority on an adjudicator’s entitlement to fees when he or she resigns. For what it is worth, by analogy with paragraph 9(4) of the Scheme, I have previously suggested (at paragraph 10-27 of the 4th edition of Coulson on Construction Adjudication) that there may well be such an entitlement. In Paul Jensen Ltd v Staveley Industries PLC, 27 September 2001 (unreported but cited in that paragraph), District Judge Donnelly said that it did not matter whether the adjudicator had been right or wrong to resign because of a jurisdiction issue and that, because there was no suggestion of default or misconduct on the adjudicator’s part, the adjudicator was entitled to the fees incurred prior to his resignation. In the recent Supreme Court decision on the topic, it was made plain that, depending on the circumstances of the case, an act of bad faith will usually require some measure of dishonesty or unconscionability: see Pakistan International Airline Corp v Times Travel (UK) Ltd [2021] UKSC 40; [2021] 3 W.L.R. 727.’ The judgement at first instance in the TCC and on appeal to the Court of Appeal accompany this newsletter and I would encourage you to read them.

- 12. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 12 | P a g e ADJDUCIATORS LONDON 2021 ADJDUCIATION & ARBITRATION CONFERENCE The conference was another great success with attendess from across the globe. If you want to view the six panels videos or read the conference pack please go to the UK Adjudicators website. https://www.ukadjudicators.co.uk/conferenc es

- 13. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 13 | P a g e TCC COURT JUDGEMENTS January • Atos Services UK Ltd v Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy & Anor [2022] EWHC 42 (TCC) (17 January 2022) • Avantage (Cheshire) Ltd & Ors v GB Building Solutions Ltd & Ors [2022] EWHC 171 (TCC) (31 January 2022) • Bilton & Johnson (Building) Co Ltd v Three Rivers Property Investments Lt [2022] EWHC 53 (TCC) (14 January 2022) • Cambridgeshire County Council v Bam Nuttall Ltd & Ors [2022] EWHC 275 (TCC) (18 January 2022) • Good Law Project Ltd & Anor, R (On the Application Of) v The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care [2022] EWHC 46 (TCC) (12 January 2022) • Hirst & Anor v Dunbar & Ors [2022] EWHC 41 (TCC) (14 January 2022) • John Graham Construction Ltd v Tecnicas Reunidas UK Ltd [2022] EWHC 155 (TCC) (27 January 2022) • Lumley v (1) Foster & Co Group Ltd & Ors [2022] EWHC 54 (TCC) (14 January 2022) • Qatar Airways Group QCSC v Airbus [2022] EWHC 285 (TCC) (20 January 2022) • The Sky's the Limit Transformations Ltd v Mirza [2022] EWHC 29 (TCC) (10 January 2022) • Transparently Ltd v Growth Capital Ventures Ltd [2022] EWHC 144 (TCC) (26 January 2022) February • Naylor & Ors v Roamquest Ltd & Anor [2022] EWHC 277 (TCC) (02 February 2022) • Struthers & Anor v Davies (t/a Alastair Davies Building) & Anor [2022] EWHC 333 (TCC) (18 February 2022)

- 14. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 14 | P a g e The DRBF International Conference will be taking place in London in 6 – 8 May 2022. Leading speakers, lawyers, experts, clients, dispute board members, dispute board users and contractors will be attending. https://www.drb.org/ FORTHCOMING EVENTS Monday, February 28, 2022 - 1:00 PM How Our Cities Survive Earthquakes: An introduction to seismic engineering for the construction law professional Online Chair: Sarah Williams, Keating Chambers Speaker(s): Dr Troy Morgan, Exponent For more info Tuesday, March 1, 2022 - 6:30 PM The Building Safety Bill: what is it? where is it at? who is impacted? will it deliver? London Chair: Jonathan Pawlowski Moderator: Zoe de Courcy, Infrastructure Sector Partner Speaker(s): Panellists - Katherine Metcalfe, Legal Director at Pinsent Masons specialising in advice on health and safety, fire safety and environmental matters; Charmaine McQueen-Prince, In House Counsel, HomeGround Management Ltd ;Pete Wise, Technical

- 15. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 15 | P a g e Director of Fire Engineering, Part B specialising in fire engineering, fire risk management and operational firefighting Venue: National Liberal Club and Online For more info Wednesday, March 2, 2022 - 9:00 AM Third party funding in 2022: the lawyer, the arbitrator and the funder's view Online Moderator: Michael Dillon - Horizons & Co Speaker(s): Joe Durkin - LCM Finance, Marion Smith QC - 39 Essex Chambers, Hamish Lal - Akin Gump & Colin Monaghan - Mason Hayes Curran For more info Friday, March 4, 2022 - 8:15 AM The Society of Construction Law Annual Spring Conference 2022 Leeds Speaker(s): Mrs Justice O'Farrell DBE, Ryan Turner - Atkin Chambers, John Riches - Henry Cooper Consultants Ltd, Tom Owen - Keating Chambers, Michael Levenstein and David Pliener - Gatehouse Chambers Venue: The Royal Armouries, Armouries Drive, Leeds LS10 1LT Full details in this flyer For more info Monday, April 4, 2022 - 9:00 AM The Use of Technology in International Construction Arbitrations Online Moderator: Sara Koleilat-Aranjo - Al Tamimi & Company Speaker(s): Ben Giaretta - Fox Williams, Dr Yazan D Haddadin - Seraj Law & Mariana Verdes - Law Library For more info Tuesday, April 5, 2022 - 6:30 PM Memorial Talk John Sims and Ray Turner London Speaker(s): Rowan Planterose and John Tackaberry QC Venue: National Liberal Club and Online For more info Tuesday, May 10, 2022 - 6:30 PM Contract Damages for Defective Construction Work: An Unsolved Puzzle? London Chair: Jonathan Cope Speaker(s): Dr Matthew Bell, Associate Professor and Co-Director of Studies for Construction Law, University of Melbourne Venue: National Liberal Club and Online For more info

- 16. WWW.UKADJUDICATORS.CO.UK FEBRUARY 2022 NEWSLETTER 16 | P a g e THE SOCIETY OF CONSTRUCTION LAW NORTH AMERICA The Society of Construction Law North America (SCL-NA) is hosting their annual conference from the 6th to the 8th of July 2022 at the beautiful Omni Interlocken Resort in Broomfield, Colorado just 18 miles northwest of downtown Denver. https://scl-na-conference.org/ SCL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE 2023 The Society of Construction Law 10th International Conference will be hosted by SCL Turkey in Istanbul in 2023. Wednesday, March 2, 2022 Third party funding in 2022: the lawyer, the arbitrator and the funder's view Joint SCL & the Adjudication Society online event Thursday, May 26, 2022 Adjudication Case Law Update No.4 This is the fourth lecture in which practitioners and adjudicators will provide an all-you-need-to-know update on recently decided adjudication case law. Monday, June 27, 2022 Adjudication Society Golf Day 2022 The second Adjudication Society Golf Day is open to members of the Adjudication Society only.

- 17. Dispute Boards are recognized worldwide for their effectiveness in the real time avoidance and resolution of disputes on major projects. Embraced by government agencies, private project owners, and funding agencies, Dispute Boards contribute to project success through significant decreases in costs and time overruns. Join other professionals at the DRBF’s premier international educational and networking event to learn the latest about Dispute Boards (DBs) across the world. This year delegates can join this international gathering in one of two ways: full two-day event in person, or one day virtual. The program is intentionally designed to give great value to virtual attendees, and maximize the benefits of in person events with robust interactive sessions and networking. There are alsotwooptionalworkshopsofferedon9MayforconstructionattorneysandadvancedDBpractitioners. In-Person and Online Event To receive an invitation and learn more, Experienced professionals will discuss Dispute Board practice within the context of: Sustainability and environmental initiatives Moving beyond ‘tick the box’ DBs to robust implementation of the process Lessons learned from case studies across the world including metros/transit, PPP projects, and more Peer discussion roundtables: contractor perspective, corruption, pandemic-related claims, dispute avoidance techniques, and more Plus the popular mock Dispute Board to demonstrate procedure with a spotlight on the DB’s role with regards to World Bank initiatives. join our mailing list. Visit www.DRB.org or email us: info@drb.org. Dispute Boards Worldwide Accelerating implementation in 2022 and beyond Location: St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel London, UK

- 18. Case No: HT-2021-000006 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS OF ENGLAND AND WALES TECHNOLOGY AND CONSTRUCTION COURT (QBD) [2021] EWHC 1337 (TCC) Royal Courts of Justice Rolls Building London, EC4A 1NL Date: Wednesday 19th May 2021 Before : MR ROGER TER HAAR QC Sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: DAVIES & DAVIES ASSOCIATES LIMITED Claimant - and – STEVE WARD SERVICES (UK) LIMITED Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Nigel Davies (a director of the Claimant Company) for the Claimant James Bowling (instructed by Costigan King) for the Defendant Hearing date: 23 April 2021 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. Covid-19 Protocol: This judgment will handed down by the judge remotely by circulation to the parties’ representatives by email and release to Bailii. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 10.30am on Wednesday 19th May 2021. .............................

- 19. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S Mr Roger ter Haar QC : 1. There is before me an application on the part of the Claimant for summary judgment for the fees of Mr. Nigel Davies for acting as the Adjudicator in an Adjudication brought by the Defendant against Bhavishya Investment Ltd (“BIL”). 2. Although Mr Davies was the Adjudicator, his fees, if payable, were payable to the Claimant. Hereafter I refer to Mr Davies as “the Adjudicator” save where I am recording submissions he made before me as representative of the Claimant. 3. The claim (in the sum of £4,290 plus VAT) is for a very small amount of money by the standard of claims which come before this Court. It raises interesting points as to the circumstances in which an Adjudicator’s fees are or are not payable. The Facts 4. In late 2019 – early 2020 the Defendant carried out construction operations at a restaurant called “Funky Brownz”, 28 Belmont Circle, Kenton Lane, Stanmore, Middlesex (the Premises). 5. The Premises are owned and operated by BIL as “Funky Brownz”. 6. At all material times one Ms Vaishali Patel was a director and the majority shareholder in BIL. 7. In late 2019 a set of contract documents was drawn up but not signed. 8. At the head of the proposed contract is a section which reads as follows: “CLIENT VAISHALI PATEL FUNKY BROWNZ 28 Belmont Circle, Belmont Circle Kenton Lane Stanmore, Middlesex, United Kingdom, HA3 8RF (the “Client”)” 9. Clause 1 of the proposed contract provided: “The Client hereby agrees to engage the Contractor to provide the Client with the following services (the “Services”): • DESIGN SUPPLY AND BUILD OF FUNKY BROWNZ 28 Belmont Circle, Belmont Circle Kenton Lane, Stanmore, Middlesex, United Kingdom, HA3 8RF, Internal decorations.”

- 20. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S 10. At the end of the proposed contract, it provided for a seal to be affixed: “IN WITNESS WHEREOF the Parties have duly affixed their signatures under hand and seal on this ___ day of _______ ____ “Client “FUNKY BROWNZ “Per ____________ (Seal) Attention: OWNER/PROPITIER MISS VAISHALI PATEL.” (The mistyping of the word “Proprietor” is in the original.) 11. As I have said, the contract was never signed. Invoices for the works as they progressed were however addressed to and paid by BIL. 12. As at completion of the works in February 2020, the Defendant claimed an unpaid balance of £35,974.29. 13. The parties then fell into dispute about whether the works were complete, defects and snags. 14. It is the Defendant’s case that it asked for access to carry out any works required in order to be paid. Access was finally secured on 18 May 2020. The Defendant said it completed the defects notified. 15. However, payment was still not made: it was claimed that the remedial works were defective and the works were still incomplete. These exchanges about access and defects took place between about April 2020 and at least June 2020 between solicitors for the Defendant and those representing Funky Brownz (I put it this way so as not to pre-judge who was the Defendant’s counterparty). 16. The Defendant says that all of those communications were on the basis that BIL was the contracting party liable for any sums due. At no stage did BIL suggest that Ms Patel was personally liable instead. 17. On 15 April 2020 the Defendant served a Statutory Demand upon for the unpaid sums. The Statutory Demand was directed at BIL. Claims consultants engaged by BIL threatened an injunction to restrain presentation of a petition on the basis that the debt was bona fide disputed because of the defects, but not on the additional ground that BIL was not the relevant contracting party. 18. The Defendant therefore withdrew the Statutory Demand. 19. Under cover of an e-mail dated 14 September 2020, the Defendant’s solicitors, Costigan King, submitted a request to The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (“RICS”) dated 14 September 2020 for the nomination of a construction adjudicator under the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998 SI No.649 (as amended) (“the Scheme”) and the CIC Low Value Disputes Model Adjudication

- 21. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S Procedure (“the Model Procedure”) in relation to a dispute said to be with BIL. Costigan King then sent the Notice of Adjudication to BIL by e-mail of the same date. 20. On 15 September 2020 the Adjudicator was nominated by the RICS to act as the Adjudicator under the Scheme and the Model Procedure in relation to a dispute defined as being between the Defendant and BIL. 21. This was the first of two adjudications. The application before me concerns the second adjudication referred to below. 22. On the same date, 15 September, the Adjudicator wrote to the parties by post and e- mail providing directions and copies of his terms and conditions by letter. Costigan King acknowledged receipt of the letter and e-mail under cover of their e-mail of the following day, 16 September 2020. 23. I refer to the Adjudicator’s terms and conditions in more detail below. They were the same in respect of both adjudications. 24. Neither party objected to those terms and conditions. 25. Under cover of an e-mail dated 21 September 2020 BIL disputed that the Adjudicator had jurisdiction to decide the dispute in the first adjudication on the grounds that the request for nomination of an adjudicator was made to the RICS before the Notice of Adjudication had been issued by the Defendant to BIL. 26. By email on 21 September 2020 the Adjudicator resigned as adjudicator in the first adjudication. 27. The Claimant rendered to the Defendant an invoice for 1.7 hours of the Adjudicator’s time. The Defendant paid this invoice. 28. On behalf of the Defendant, Costigan King issued BIL with a second Notice of Adjudication dated 21 September 2020 and a second request to the RICS followed on 22 September 2020 for the nomination of a construction adjudicator under the Scheme and the Model Procedure. 29. On 23 September 2020 the Adjudicator was nominated again by the RICS to act as Adjudicator under the Scheme and the Model Procedure in relation to the same dispute between the Defendant and BIL. 30. Again, the Adjudicator wrote to the parties providing directions and copies of his terms and conditions by letter sent by post and e-mail dated 23 September 2020. His terms and conditions were identical to those which he had issued to the parties eight days earlier on 15 September 2020. Again, there was no objection to his terms and conditions. 31. The Adjudicator received the Response on 8 October 2020 and the Reply on 15 October 2020. 32. In his Skeleton Argument for the hearing before me, Mr Davies set out what happened next as follows:

- 22. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “23. The Response was received on 8 October 2020 …. and the Reply was received on 15 October 2020 …. “24. In accordance with Referral para.4 … the Defendant claimed the Parties to the adjudication had entered into “the Contract” pursuant to an agreement in writing on or around 21 November 2019 …. “25. The Contract …. the Defendant had written and relied upon in order to bring the adjudication, unequivocally recorded that it was between the Defendant and Miss Vaishali Patel and it contained both a “Modification of Agreement” clause at para.24 and at para.27 an “Entire Agreement” clause ... Despite exhaustive enquiries of the documents and of the Parties as per my e-mail dated 16 October 2020 timed 1759hrs …. I established that the Contract had not ever changed (e.g. by novation) and remained to be between the Defendant and Miss Patel. “26. Para.12(b) of Part 1 of the Scheme …. provides that I was to avoid incurring unnecessary expense. Following e-mail correspondence with the Parties dated 15 and 16 October 2020 consistent with para.9 of Part 1 of the Scheme … and para.31 of the CIC LVD MAP … I resigned as the Adjudicator by e-mail dated 16 October 2020 timed 1759hrs …. I resigned because Bhavishya was not a Party to and/or identified within the Contract on which basis the second adjudication had been referred and therefore I was without jurisdiction as per paragraph 31 in Dacy Building Services Ltd v IDM Properties LLP [2016] EWHC 3007 (TCC) (25 November 2016) …. and paragraphs 62 to 64 of the judgment in M Hart Construction Ltd & Anor v Ideal Response Group Ltd (Rev 1) [2018] EWHC 314 (TCC) (07 March 2018) …. “27. Clearly, I could not issue a Decision in relation to the contractual rights of one of the contracting parties in an adjudication where the other contracting party was not a party to the process. Obviously, Bhavishya’s participation did not change this. “28. It had been necessary to establish such facts because at Referral para.39 … the Defendant had requested that I provide written reasons for my Decision and because it was a critical component to my reasoning. It was a natural consequence of establishing whether and on what basis the Defendant was entitled to the payment it claimed from Bhavishya, all in accordance with para.13 of Part 1 of the Scheme …., i.e. take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law necessary to determine the dispute. It was part of the process of determining the adjudication as per paragraph 38 in Ex Novo Limited v MPS Housing Ltd [2020] EWHC 3804 (TCC) (17 December 2020) ….

- 23. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “29. I issued the Claimant’s invoice number 696 in the VAT inclusive sum of £5,148 …. in accordance with my accepted terms and conditions …., addressed to the Defendant, by e-mail to Costigan King dated 19 October 2020 timed 1122hrs ….. “30. Under cover of my e-mail dated 21 October 2020 timed 1654hrs, I provided a breakdown of my time charged under invoice number 696 …. and …. Out of the 16.9 hours spent I charged for 13.2 hours.” 33. On 20 October 2020 Costigan King wrote by email to say that the Defendant would not pay the Claimant’s invoice because it was claimed that Mr Davies had committed a repudiatory breach of his contract of appointment. The Defendant was said to have accepted the Adjudicator’s repudiation so that his terms and conditions had ceased to have effect. It was also claimed that the Claimant was not entitled to payment because of the Court of Appeal decision in PC Harrington Contractors Limited v Systech International Limited [2012] EWCA Civ 1371. The Adjudicator’s Terms and Conditions 34. The covering letters to the Adjudicator’s two appointments made clear that any fees charged would be paid through the Claimant company. 35. The following were the material provisions of the Adjudicator’s terms and conditions: “Basis of Charge “Time related for hours expended working or travelling in connection with the Adjudication including all time up to settlement of any Fee Invoice, which, for the avoidance of doubt, may include any time including Court time, spent securing payment of any fees, expenses and disbursements due. “Amount of Charge “The Adjudicator’s (Nigel J. Davies) fee shall be charged in accordance with the CIC LVD MAP current as at the date of this letter as set out in Schedule 1 thereto. Should the said CIC LVD MAP cease to apply then the amount of charge for the Adjudicator shall be £325 per hour applied on an ab initio basis, i.e. it will be applied from the date of the Adjudicator’s nomination by the RICS. “In any event the CIC LVD MAP shall no longer apply from the point at which a CIC LVD MAP Decision is delivered and thereafter the £325 per hour charge shall apply, e.g. in relation to securing unpaid fees, expenses and disbursements due. “…. “Frequency of Charge

- 24. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “A Fee Invoice will be raised and is due for payment 7 days thereafter. “In the event of the Adjudication ceasing for any reason whatsoever prior to a Decision being reached, a Fee Invoice will be raised immediately and is due for payment 7 days after the date of the Invoice. “In the event of any invoice not being settled as stated an additional charge may be raised for interest charges, which charges will be calculated at the rate of 2.5% per calendar month or pro-rata any part thereof, for the period between the date of invoice and the date of payment in full of that invoice. “Miscellaneous Provisions: “1. The Parties agree jointly and severally to pay the Adjudicator’s fees and expenses as set out in this Schedule. Save for any act of bad faith by the Adjudicator, the Adjudicator shall also be entitled to payment of his fees and expenses in the event that the Decision is not delivered and/or proves unenforceable. “… “3. The Parties acknowledge that the Adjudicator shall not be liable for anything done or omitted in the discharge or purported discharge of his functions as Adjudicator (whether in negligence or otherwise) unless the act or omission is in bad faith, and any employee or agent of the Adjudicator shall be similarly protected from liability. “4. The Adjudicator is appointed to determine the dispute or disputes between the Parties and his decision may not be relied upon by third parties, to whom he shall owe no duty of care….” The Scheme 36. The statutory scheme for adjudication is contained in the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations 1998 (SI 1998 No. 649) as amended. 37. Paragraph 9 provides: “(1) An adjudicator may resign at any time on giving notice in writing to the parties to the dispute. “(2) An adjudicator must resign where the dispute is the same or substantially the same as one which has previously been referred to adjudication, and a decision has been taken in that adjudication. “(3) Where an adjudicator ceases to act under paragraph 9(1) –

- 25. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “(a) the referring party may serve a fresh notice under paragraph 1 and shall request an adjudicator to act in accordance with paragraphs 2 to 7; and “(b) if requested by the new adjudicator and insofar as it is reasonably practicable, the parties shall supply him with copies of all documents which they had made available to the previous adjudicator. “(4) Where an adjudicator resigns in the circumstances referred to in paragraph (2), or where a dispute varies significantly from the dispute referred to him in the referral notice and for that reason he is not competent to decide it, the adjudicator shall be entitled to the payment of such reasonable amount as he may determine by way of fees and expenses reasonably incurred by him. Subject to any contractual provision pursuant to section 108A(2) of the Act, the adjudicator may determine how the payment is to be apportioned and the parties are jointly and severally liable for any sum which remains outstanding following the making of any such determination.” 38. Paragraph 11 provides: “(1) The parties to a dispute may at any time agree to revoke the appointment of the adjudicator. The adjudicator shall be entitled to the payment of such reasonable amount as he may determine by way of fees and expenses incurred by him. Subject to any contractual provision pursuant to section 108A(2) of the Act, the adjudicator may determine how the payment is to be apportioned and the parties are jointly and severally liable for any sum which remains outstanding following the making of any such determination. “(2) Where the revocation of the appointment is due to the default or misconduct of the adjudicator, the parties shall not be liable to pay the adjudicator’s fees and expenses.” 39. Paragraph 12 provides: “The adjudicator shall – “(a) act impartially in carrying out his duties and shall do so in accordance with any relevant terms of the contract and shall reach his decision in accordance with the applicable law in relation to the contract; and “(b) avoid incurring unnecessary expense.” 40. Paragraph 13 provides:

- 26. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “The adjudicator may take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law necessary to determine the dispute, and shall decide on the procedure to be followed in the adjudication…..” 41. Paragraph 20 provides: “The adjudicator shall decide the matters in dispute. He may take into account any other matters which the parties to the dispute agree should be within the scope of the adjudication or which are matters under the contract which he considers are necessarily connected with the dispute ….” 42. Paragraph 25 provides: “The adjudicator shall be entitled to the payment of such reasonable amount as he may determine by way of fees and expenses reasonably incurred by him. Subject to any contractual provision pursuant to section 108A(2) of the Act, the adjudicator may determine how the payment is to be apportioned and the parties are jointly and severally liable for any sum which remains outstanding following the making of any such determination.” 43. Paragraph 26 provides: “The adjudicator shall not be liable for anything done or omitted in the discharge or purported discharge of his functions as an adjudicator unless the act or omission is in bad faith, and any employee or agent of the adjudicator shall be similarly protected from liability.” PC Harrington Contractors Limited v Systech International Limited 44. In any dispute concerning whether an adjudicator is entitled to his or her fees, the starting point is almost always the Court of Appeal decision in PC Harrington Contractors Ltd v Systech International Ltd [2012] EWCA Civ 1371; [2013] Bus LR 970; [2013] BLR 1. 45. In PC Harrington the adjudicator was found in each of three references to have reached a conclusion in breach of his duty to comply with the rules of natural justice in that he failed to decide a relevant issue raised by way of defence because he took what was later held to have been an erroneous view as to jurisdiction. The consequence was that the decisions were unenforceable. 46. The question which arose was whether the adjudicator was entitled to his fees for producing unenforceable decisions. At first instance Akenhead J. decided that he was. The Court of Appeal took the opposite view and allowed an appeal. 47. In his judgment the Master of the Rolls said this: “[32] I return to the question: what was the bargained-for performance? In my view, it was an enforceable decision. There is nothing in the contract to indicate that the parties agreed that

- 27. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S they would pay for an unenforceable decision or that they would pay for the services performed by the adjudicator which were preparatory to the making of an unenforceable decision. The purpose of the appointment was to produce an enforceable decision which, for the time being, would resolve the dispute. A decision which was unenforceable was of no value to the parties. They would have to start again on a fresh adjudication in order to achieve the enforceable decision which Mr Doherty had contracted to produce. “[33] Para 11(2) of the Scheme provides powerful support for PCH’s case. If the adjudicator’s appointment is revoked due to his default or misconduct, he is not entitled to any fees. It can hardly be disputed that the making of a decision which is unenforceable by reason of a breach of the rules of natural justice is a “default” or “misconduct” on the part of an adjudicator. It is a serious failure to conduct the adjudication in a lawful manner. If during the course of an adjudication, the adjudicator indicates that he intends to act in breach of natural justice (for example, by making it clear that he intends to make a decision without considering an important defence), the parties can agree to revoke his appointment. In that event, the adjudicator is not entitled to any remuneration. It makes no sense for the parties to agree that the adjudicator is not entitled to be paid if his appointment is revoked for default or misconduct before he makes his purported decision, but to agree that he is entitled to full remuneration if the same default or misconduct first becomes manifest in the decision itself. I would not construe the agreement as having that nonsensical effect unless compelled to do so by express words or by necessary implication. I can find no words which yield such a meaning either expressly or by necessary implication. “[34] The fact that the adjudicator was not liable for anything done or omitted to be done unless it was in bad faith (para 26) lends further support to the view that the parties did not intend that the adjudicator should be paid for producing an unenforceable decision. If Miss Rawley is right, the adjudicator was entitled to be paid the same fee for producing an unenforceable decision as for producing one that was enforceable and yet, absent bad faith, the parties are not able to claim damages for the adjudicator's failure to produce an enforceable decision, regardless of the seriousness of the failure and the loss it has caused. That is a most surprising bargain for the parties to have made. I would be reluctant to impute to them an intention to make such a bargain unless compelled to do so. I can find nothing in the terms of engagement or the Scheme which compels the conclusion that this was their intention. “The position of judges and arbitrators

- 28. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “[35] As I have said, the judge seems to have found support for his conclusion that the functions performed by an adjudicator which are ancillary and anterior to the making of a decision are valuable in their own right by comparing the position of adjudicators with that of arbitrators and judges: see para 12 above. Miss Rawley has not relied on this part of the judge's reasoning. I think that she is right not to do so. A judge has an inherent jurisdiction and does not derive his powers over a dispute from a contract of appointment. That is sufficient to render any comparison with a judge wholly inapposite. “[36] At first sight, the comparison with the position of arbitrators might seem to be more fruitful, since they derive their authority from a contract with the parties. But as Mr Bowling points out, there are important differences between adjudicators and arbitrators. First and foremost, serious errors and fundamental misunderstandings by an arbitrator do not invalidate his award. The award is binding, subject to the supervisory jurisdiction of the court under sections 66-68 of the Arbitration Act 1996. Secondly, when anterior and ancillary functions are carried out by an arbitrator, they are binding on the parties (and therefore the arbitrator gives value in performing them). If the arbitrator ceases to hold office during the course of a reference, the parties are free to agree whether and, if so, how the vacancy is to be filled and whether and, if so, to what extent the previous proceedings should stand: see section 27 of the Act. This is to be contrasted with the position in an adjudication: if the adjudicator's appointment is terminated (for whatever reason), the process must be started again with a fresh referral. Thirdly, an arbitrator has inherent jurisdiction and power to make a binding decision on the scope of his own jurisdiction, unless the parties otherwise agree: section 30 of the Act. An arbitrator, unlike an adjudicator, can give value by providing a binding ruling on his jurisdiction. “Policy considerations “[37] Finally, I should deal briefly with the judge's recourse to policy considerations. I accept that the statutory provisions for adjudication reflect a Parliamentary intention to provide a scheme for a rough and ready temporary resolution of construction disputes. That is why the courts will enforce decisions, even where they can be shown to be wrong on the facts or in law. An erroneous decision is nevertheless an enforceable decision within the meaning of the 1996 Act and the Scheme. But a decision which is unenforceable because the adjudicator had no jurisdiction to make it or because it was made in breach of the rules of natural justice is quite another matter. Such a decision does not further the statutory policy of encouraging the parties to a construction contract to refer their disputes for

- 29. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S temporary resolution by an adjudicator. It has quite the opposite effect. It causes the parties to incur cost and suffer delay on a futile exercise. I can see no basis for holding that Parliament must have intended that an adjudicator who produces an unenforceable decision should be entitled to payment. As I have attempted to show, Parliament did address the question of remuneration in the Scheme and produced a carefully calibrated set of provisions. I suppose that Parliament could have provided that an adjudicator was entitled to reasonable remuneration even where he produced an unenforceable decision, although this possibility seems rather fanciful to me. But it did not do so. I do not consider that it is legitimate, in effect, to rewrite the Scheme on the basis of some unarticulated Parliamentary policy grounds.” 48. In his judgment, Davis L.J. said: “[40] In the present case, as Akenhead J found at the earlier hearing, the adjudicator – albeit acting in good faith – entirely failed to deal with a defence raised which (if valid, which it may or may not have been) would have defeated Tyroddy's claims. Further, he failed first to advise the parties of his intended approach or seek their submissions. So it can properly be said that there was here a breach of the rules of natural justice constituting a "default" of which he was the author. But it will not always be so. For example, the logic of Mr Bowling's argument would, as he accepted, apply – absent specific contractual terms to the contrary – to cases where, for example, an adjudicator, having done a considerable amount of work, died or was struck down with serious incapacitating illness before a decision could be produced at all. “[41] That said, in my view the key nevertheless is to consider what was the contractual bargain actually made. To say in general terms, as Mr Bowling did as an opening observation, that the law does not require people to pay for worthless things is not necessarily right as a generalisation and is wrong in failing to focus on what the actual terms of the contract are. I in fact did not regard either counsel's respective appeals to the asserted merits very helpful. All depends on the contract actually made. “[42] To me, what effectively decides the matter in favour of the appellant are the terms of the Scheme itself. As the Master of the Rolls has explained, the terms of paragraph 9 and of paragraph 11 – and in particular the intention behind and implications of paragraph 11(2) – indicate that the conclusion for which Mr Bowling contended is the correct one. Nor do the Terms of Engagement employed by Mr Doherty and incorporated into this particular contract indicate any different conclusion.

- 30. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “[43] I also would attach significant weight to paragraph 20 of the Scheme. That expressly stipulates that the adjudicator shall decide the matters in dispute. But where, as here, an adjudicator delivers a decision which is entirely unenforceable then he will not have decided the matters in dispute. On Miss Rawley's argument the parties – absent an express term – not only have no redress for any loss (in that the Scheme excludes any warranty on the part of the adjudicator and excludes any liability for acts done or omitted, absent bad faith) they also must pay the adjudicator's fees notwithstanding that the adjudicator has not decided the matters in dispute. In my view, that would be surprising and is also an indicator in favour of Mr Bowling's argument. “[44] As to the special situation arising in an adjudication where one of the parties raises a challenge on jurisdiction before a decision is reached and then, having received the adjudicator's ruling on jurisdiction, elects that the adjudicator should proceed to a decision, that situation is in my view correctly addressed by Ramsey J at paragraphs 76 to 79 of his judgment in Linnett v Halliwells LLP [2009] EWHC 319 (TCC), [2009] BLR 312. The adjudicator's fees are then – subject of course to any express terms agreed – payable even if the Court subsequently were to declare the initial challenge to the jurisdiction to have been well- founded. “[45] I therefore would conclude in the present case that the adjudicator is not entitled to be paid any fees. He has not produced an (enforceable) decision which determines the matters in dispute: which is what this contract required of him before his entitlement to fees arose. “[46] I doubt if the present decision should have any very great ramifications. Prior to this case, I personally had had little acquaintance with the adjudication Scheme under the 1996 Act. It appears, from what we were told, generally to be working very well indeed – and not least, I suspect, because of the short prescribed time limits and the splendid "pay now, argue later" approach, which is thoroughly to be commended. At all events in the fifteen years or so since the scheme has been operating this particular kind of dispute about fees seems, as we were told, not previously to have surfaced in the courts. In any case, if this decision does give rise to concerns on the part of adjudicators then the solution is in the market-place: to incorporate into their Terms of Engagement (if the parties to the adjudication are prepared to agree) a provision covering payment of their fees and expenses in the event of a decision not being delivered or proving to be unenforceable. It is of course a consequence of this court's conclusion that it is for the adjudicator to stipulate for such a

- 31. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S term: not for the parties to the adjudication to stipulate to the contrary.” 49. Mr Davies told me that the terms and conditions upon which the Claimant relies were drafted in the light of Davis L.J.’s judgment. The Issues before the Court 50. In his skeleton argument, Mr Bowling, for the Defendant, identifies the issues before the Court as follows: (1) Whether there was a threshold point of jurisdiction before the Adjudicator pursuant to which he was entitled to resign, or whether the Adjudicator’s decision to do so represented abandonment of his appointment and a deliberate and impermissible refusal to provide a Decision1 . (2) The proper construction of the following clauses in the Adjudicator’s standard terms, which the Adjudicator claims entitle him to payment for work done to the point of abandonment, the lack of a Decision notwithstanding: a) Clause 1 of the Adjudicator’s standard terms (“Save for any act of bad faith by the Adjudicator, the Adjudicator shall … be entitled to payment of his fees and expenses in the event that the Decision is not delivered and/or proves unenforceable”2 ); and b) The unnumbered clause stating that “In the event of the Adjudication ceasing for any reason whatsoever prior to a Decision being reached, a Fee Invoice will be raised immediately and [become] due for payment …” (3) If those clauses are effective in the manner the Adjudicator contends, whether they are nevertheless void under s3(2)(b) of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977. (4) If a fee is payable, whether 13.20hrs is excessive given the amount of work done on the application of Fenice Investments v Jerram Falkus Construction [2011] EWHC 1678 (TCC). Issue No. 1: Was there a threshold jurisdictional issue? 51. The Adjudicator took the view that it was clear that the underlying contract was between the Defendant and Ms Patel, not between the Defendant and BIL. 52. If that was the correct view, then, subject to waiver on the part of BIL, the Adjudicator was correct in deciding that he had no jurisdiction over the dispute: Dacy Building Services Ltd v IDM Properties Ltd [2016] EWHC 3007 (TCC); [2017] BLR 114 and M Hart Construction Ltd & Anor v Ideal Response Group Ltd [2016] EWHC 3007 (TCC). 1 Defence para 12 [21] 2 [96]

- 32. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S 53. To that extent, I did not understand Mr Bowling to dissent. However he submitted, firstly, that the preponderance of evidence showed that BIL, rather than Ms Patel, was the contracting party. 54. I do not accept this first argument. The Referral clearly placed the case upon the basis that the contract was a contract in writing. Whilst the proposed contract was unsigned, it clearly envisaged that the contract would be between the Defendant and Ms Patel. I also note that the Defence in this action did not contend that the construction contract was with BIL. 55. On the evidence before him, it seems to me at the lowest the Adjudicator was entitled to conclude that the contract was with Ms Patel, not BIL. 56. Secondly Mr Bowling argues that in any event, there was submission to the jurisdiction by BIL. By paragraphs 4 – 11 of the Referral SCS made a clear allegation that the construction contract was with BIL. The Response did not dispute that, concentrating on BIL’s allegations of defects in the works provided to it, together with BIL mounting a counterclaim for some £82,768.20. Mr Bowling submits that the submission of a Response in these terms amounted to a clear waiver of any threshold jurisdictional point based on an allegation that the contract was with Ms Patel instead; see Brims v A2M [2013] EWHC 3262 (TCC) and Thomas-Fredric’s (Construction) Limited v Keith Wilson [2004] BLR 24 per Simon Brown LJ at [31]. 57. In my view, based upon those decisions, it was probably the case that if after the Adjudicator had issued a decision, BIL were to suggest that the Adjudicator did not have jurisdiction to issue that decision upon the basis that BIL was a not a party to the contract, BIL would be held to have waived the right to pursue such a jurisdictional argument. 58. Developing that argument, Mr Bowling says that to the extent that a party does not adopt a jurisdictional issue (such as there may be) a fortiori it is not open to the Adjudicator to decline jurisdiction. The Adjudicator’s power to take the initiative to ascertain the facts and the law (Scheme Part I para 13) is obviously to be exercised in the context of the dispute the parties empower the Adjudicator to decide. It is not a roving commission to identify, formulate and decide the reference on the basis of new and fundamental issues neither party raises nor adopts despite invitation. 59. I do not find this an easy point. It is undoubtedly the case that the Adjudicator has power to take the initiative, and that in this case the Adjudicator believed that he was exercising that power. Further, I accept that the Adjudicator believed that to take the initiative was consistent with his duty under paragraph 12 of the Scheme to avoid unnecessary expense. 60. In my judgment it would have been wiser for the Adjudicator not only to inquire as to the parties’ position as to who were the contracting parties, but also to inquire in terms as to whether both parties accepted that he had jurisdiction. However he did not do that. 61. The effect of what the Adjudicator did was to deprive the parties of an answer to their differences as to what sum was payable (either by Ms Patel or by BIL) in respect of the

- 33. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S project. However it is fair to say that BIL never showed any enthusiasm for this dispute to be aired. 62. The conclusion to which I have come is that the route which the Adjudicator took was outside the ambit of paragraph 13 of the Scheme: that paragraph entitles the Adjudicator to investigate matters “necessary to determine the dispute”, which necessarily involves the question, what is the dispute? At the time when the Adjudicator resigned, there was no dispute either as to the identity of the contracting parties or as to his jurisdiction. 63. Accordingly, in my view the Adjudicator’s reasoning in deciding to resign on the basis that he had no jurisdiction when that was not an issue which the parties had referred to him was erroneous. 64. However, that is not an end of the matter. It is necessary to consider whether the Adjudicator was nevertheless entitled to the fees claimed. 65. It is submitted by Mr Bowling that the Adjudicator’s decision to resign “represented abandonment of his appointment and a deliberate and impermissible refusal to provide a Decision.” 66. I do not accept that characterisation of what the Adjudicator did. Far from “abandoning his appointment”, the Adjudicator acted in accordance with what he regarded as being his duty. Far from there being a “deliberate and impermissible refusal to provide a Decision”, the Adjudicator resigned upon the basis that it was not open to him to reach a Decision in a dispute between the Defendant and BIL of the rights and obligations of a contract between the Defendant and Ms Patel. That is very far from being a “deliberate and impermissible refusal to provide a Decision”. 67. Further, resignation by an Adjudicator is not of itself a breach of the terms of the Adjudicator’s engagement since paragraph 9(1) of the Scheme permits the Adjudicator to resign at any time on giving notice to the parties: the question here is whether upon resigning the Adjudicator was still entitled to his fees. 68. In my judgment the answer to that question turns upon the true construction of the Adjudicator’s terms and conditions. Issue No. 2: the effect of the Adjudicator’s Terms and Conditions 69. The first relevant provision is in the section headed “Frequency of Charge”: “In the event of the Adjudication ceasing for any reason whatsoever prior to a Decision being reached, a Fee Invoice will be raised immediately and is due for payment 7 days after the date of the Invoice.” 70. On its face, this provision would entitle the Adjudicator to receive fees whenever the adjudication cessed, even if it ceased in circumstances where the Adjudicator was acting in bad faith. That would be a strange conclusion particularly given the terms of Clauses 1 and 3. In my judgment this clause should not be construed as entitling the Adjudicator to fees where no fees would be payable under Clause 1. This clause is in

- 34. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S a section headed “frequency of charge”, and I read the sentence I have set out in the previous paragraph as being concerned with the timing of an invoice and payment. 71. As I have already set out, Clause 1 provides: “The Parties agree jointly and severally to pay the Adjudicator’s fees and expenses as set out in this Schedule. Save for any act of bad faith by the Adjudicator, the Adjudicator shall also be entitled to payment of his fees and expenses in the event that the Decision is not delivered and/or proves unenforceable.” 72. Mr Bowling draws attention to the word “also” in the second sentence of this Clause. He distinguishes this case from cases such as those where an Adjudicator issues an unenforceable decision or produces a decision but fails to deliver it in time. Here, he says, the Adjudicator at one and the same time managed to abdicate his responsibility, exceeded his jurisdiction and failed to exhaust it. He says that this is a situation or a congeries of situations to which Clause 1 does not apply. 73. I do not agree with this submission: in my judgment the Clause means that in addition to being paid for producing a Decision (which is the normal event upon the occurrence of which an Adjudicator is entitled to payment) the Adjudicator is entitled to be paid his fees for work done unless there has been an act of bad faith on the Adjudicator’s part. 74. Mr Bowling’s next submission focuses on the meaning of the phrase “bad faith”. He submits that this should be construed as meaning “misconduct”, that is to say a situation where the Adjudicator acts in a manner which is commercially improper and which doesn’t honour or maintain fidelity to the bargain the Adjudicator has struck with the parties. 75. In support of that submission he cites the decision of Leggatt J., as he then was, in Yam Send Pte Limited v International Trade Corporation Limited [2013] EWHC 111 (QB); [2013] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 526 “[134] Importantly for present purposes, the relevant background against which contracts are made includes not only matters of fact known to the parties but also shared values and norms of behaviour. Some of these are norms that command general social acceptance; others may be specific to a particular trade or commercial activity; others may be more specific still, arising from features of the particular contractual relationship. Many such norms are naturally taken for granted by the parties when making any contract without being spelt out in the document recording their agreement. “[135] A paradigm example of a general norm which underlies almost all contractual relationships is an expectation of honesty. That expectation is essential to commerce, which depends critically on trust. Yet it is seldom, if ever, made the subject of an express contractual obligation. Indeed if a party in negotiating the terms of a contract were to seek to include a

- 35. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S provision which expressly required the other party to act honestly, the very fact of doing so might well damage the parties’ relationship by the lack of trust which this would signify. “[136] The fact that commerce takes place against a background expectation of honesty has been recognised by the House of Lords in HIH Casualty v Chase Manhattan Bank [2003] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 61. In that case a contract of insurance contained a clause which stated that the insured should have “no liability of any nature to the insurers for any information provided”. A question arose as to whether these words meant that the insured had no liability even for deceit where the insured’s agent had dishonestly provided information known to be false. The House of Lords affirmed the decision of the courts below that, even though the clause read literally would cover liability for deceit, it was not reasonably to be understood as having that meaning. As Lord Bingham put it at [15]: “Parties entering into a commercial contract … will assume the honesty and good faith of the other; absent such an assumption they would not deal.” “To similar effect Lord Hoffmann observed at [68] that “parties contract with one another in the expectation of honest dealing”, and that: “… in the absence of words which expressly refer to dishonesty, it goes without saying that underlying the contractual arrangements of the parties there will be a common assumption that the parties involved will behave honestly.” “[137] As a matter of construction, it is hard to envisage any contract which would not reasonably be understood as requiring honesty in its performance. The same conclusion is reached if the traditional tests for the implication of a term are used. In particular the requirement that parties will behave honestly is so obvious that it goes without saying. Such a requirement is also necessary to give business efficacy to commercial transactions. “[138] In addition to honesty, there are other standards of commercial dealing which are so generally accepted that the contracting parties would reasonably be understood to take them as read without explicitly stating them in their contractual document. A key aspect of good faith, as I see it, is the observance of such standards. Put the other way round, not all bad faith conduct would necessarily be described as dishonest. Other epithets which might be used to describe such conduct include “improper”, “commercially unacceptable” or “unconscionable”.

- 36. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S “[139] Another aspect of good faith which overlaps with the first is what may be described as fidelity to the parties’ bargain. The central idea here is that contracts can never be complete in the sense of expressly providing for every event that may happen. To apply a contract to circumstances not specifically provided for, the language must accordingly be given a reasonable construction which promotes the values and purposes expressed or implicit in the contract. That principle is well established in the modern English case law on the interoperation of contracts: see e.g. Rainy Sky SA v Kookmin Bank [2011] 1 WLR 2900; Lloyds TSB Foundation for Scotland v Lloyds Banking Group Plc [2013] UKSC 3 at [23, [45] and [54]. It also underlies and explains, for example, the body of cases in which terms requiring cooperation in the performance of the contract have been implied: see Mackay v Dick (1881) 6 App Cas 251, 263; and the cases referred to in Chitty on Contracts (31st Ed), Vol 1 at paras 13-012 – 13-014.” 76. Mr Bowling submits that the Adjudicator decided he was not going to decide the dispute which he had agreed to decide, and thus was not faithful to the bargain he had struck to act as Adjudicator. 77. In my view this argument bears considerable similarity to the argument which Mr Bowling successfully made to the Court of Appeal in PC Harrington v Systech. In that case the argument was that by coming to an erroneous view as to his jurisdiction to determine certain issues, the Adjudicator placed himself in a position where he delivered unenforceable decisions: in those circumstances, it was held that he was not entitled to recover his fees. 78. In that case, Davis L.J. suggested at paragraph [46] that the problem faced by an adjudicator in such a circumstance could be avoided be suitable terms in his contract of engagement: “In any case, if this decision does give rise to concerns on the part of adjudicators then the solution is in the market-place: to incorporate into their Terms of Engagement (if the parties to the adjudication are prepared to agree) a provision covering payment of their fees and expenses in the event of a decision not being delivered or proving to be unenforceable. It is of course a consequence of this court's conclusion that it is for the adjudicator to stipulate for such a term: not for the parties to the adjudication to stipulate to the contrary.” 79. I do not think it desirable in this case, where I have heard argument limited to the facts of this particular case, to discuss at any length the limits of “bad faith” in construing a clause such as Clause 1. It is sufficient for me to say that a situation such as this where an Adjudicator acting with diligence and honesty comes to the conclusion that the proper course is for him to exercise his right under Paragraph 9(1) of the Scheme to resign is not a situation within the expression “bad faith”.

- 37. Mr Roger ter Haar QC Approved Judgment D v S 80. Accordingly, my conclusion is that on the true construction of his terms and conditions, the Adjudicator was entitled to be paid for the work done by him, subject to the application of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (“UCTA”), to which I refer below. 81. Before moving to the application of UCTA, I should note another argument put forward on behalf of the Defendant: it is suggested that on analysis the parties revoked the Adjudicator’s appointment. This seems to me simply wrong on the facts. His appointment as Adjudicator came to an end upon his resignation. Thereafter there was no extant appointment to revoke. Unfair Contract Terms Act 82. The Defendant contends that if the clauses of his terms and conditions are to be construed in the manner the Adjudicator contends, they are void under section 3(2)(b) of UCTA in that they allow the Adjudicator to render performance substantially different from that contracted for. The clauses are in the Adjudicator’s standard terms of business. The starting presumption therefore is that they are void; the Adjudicator can only rely on them if he can show they satisfy the test of reasonableness. 83. Section 3 of UCTA provides: “(1) This section applies as between contracting parties where one of them deals on the other’s written standard terms of business. “(2) As against that party, the other cannot by reference to any contract term – “(a) when himself in breach of contract, exclude or restrict any liability of his in respect of the breach; or “(b) claim to be entitled – “(i) to render a contractual performance substantially different from that which was reasonably expected of him, or “(ii) in respect of the whole or any part of his contractual obligation, to render no performance at all. “except in so far as (in any of the cases mentioned above in this subsection) the contract terms satisfies the requirement of reasonableness.” 84. I have considerable doubt whether Clause 1 is caught by Section 3 of UCTA. Clause 1 is simply concerned with payment of the Adjudicator’s fees. It says nothing about what contractual performance the Adjudicator is expected to perform. In any event, paragraph 9(1) of the Statutory Scheme gives the Adjudicator an unfettered right to resign which is relevant to the contractual performance that the Adjudicator is expected to perform